.png)

The Late Bloomer Actor

Welcome to "The Late Bloomer Actor", a monthly podcast series hosted by Australian actor David John Clark.

Join David as he engages in discussions with those that have helped him on his journey as a late bloomer actor, where he shares personal stories, insights, and wisdom gained from his unique path as a late bloomer actor and the lessons he has learned, and continued to learn, from the many sources available in the acting world.

Each episode features conversations with actors and industry insiders that have crossed paths with David who generously offer their own experiences and lessons learned.

Discover practical advice, inspiration, and invaluable insights into the acting industry as David and his guests delve into a wide range of topics. From auditioning tips to navigating the complexities of the industry, honing acting skills, and cultivating mental resilience, every episode is packed with actionable takeaways to empower you on your own acting journey.

Whether you're a seasoned actor, an aspiring performer, or simply curious about the world of acting, "The Late Bloomer Actor" is here to support your growth and development. Tune in to gain clarity, confidence, and motivation as you pursue your dreams in the world of acting. Join us and let's embark on this transformative journey together!

The Late Bloomer Actor

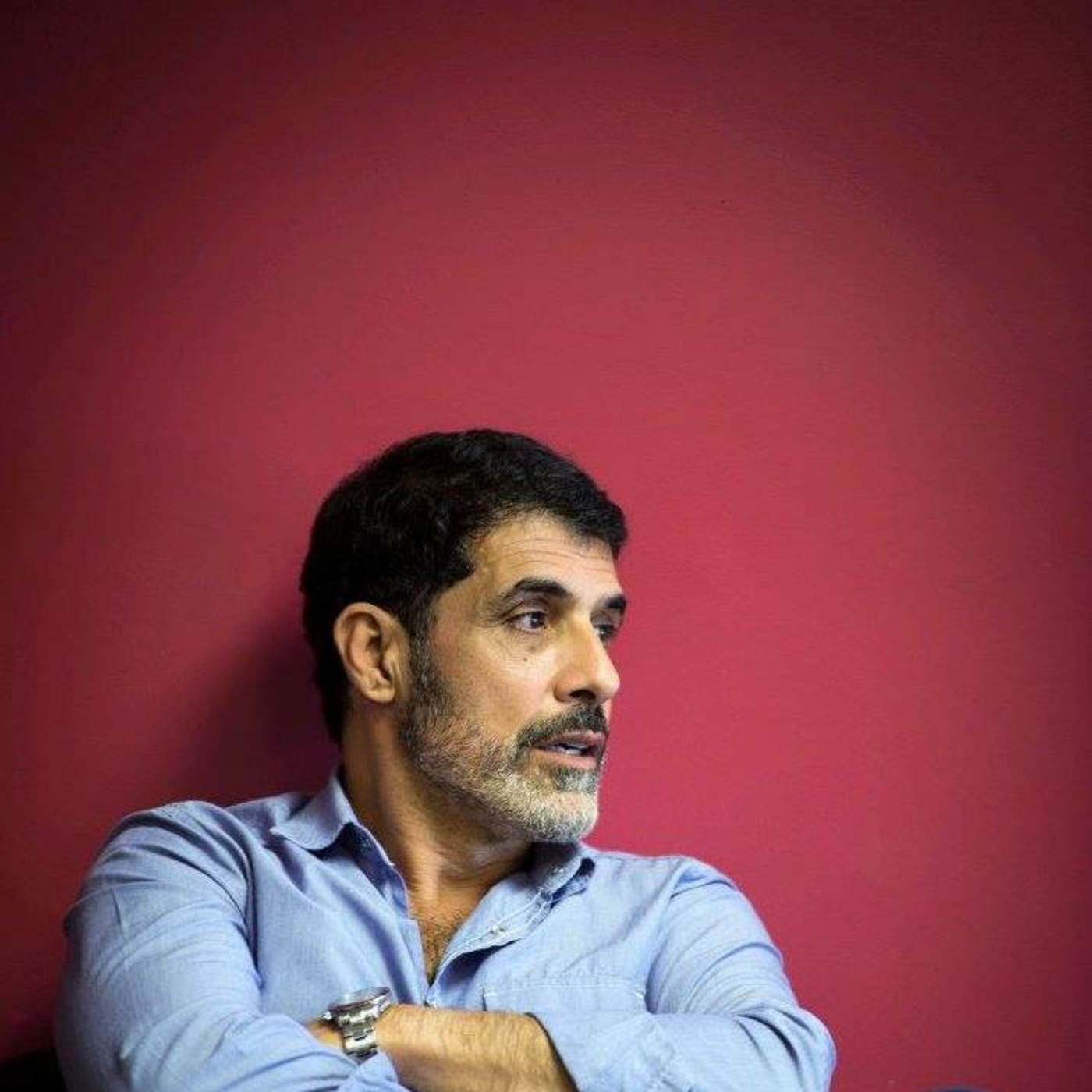

Australian TV and Film Acting with John Orcsik

Text The Late Bloomer Actor a Question or Comment.

Season 3 starts off with an awesome conversation, John Orcsik, an experienced actor and founder of TAFTA, discusses his background in acting and the evolution of the Australian television industry. He shares insights into his time working with Crawford Productions and the impact of shows like Number 96. John also talks about the importance of believability in acting and the emotions training method. He highlights the need for actors to be real and present in their performances. The conversation concludes with a discussion on TAFTA and its goals in training actors.

Takeaways

- John Orcsik has a background in acting and has worked in the Australian television industry for many years.

- He shares insights into his time working with Crawford Productions and the impact of shows like Number 96.

- John emphasizes the importance of believability in acting and the need for actors to be real and present in their performances.

- He also discusses Tafta, an organization he founded to provide training for actors.

Please consider supporting the show by becoming a paid subscriber (you can cancel at any time) by clicking here and you will have the opportunity to be a part of the live recordings prior to release.

Please follow on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and Tik Tok.

And please Rate the show on IMDB.

This episode was recorded on RiversideFM - click the link to join and record.

This episode is supported by Castability - an Audition Simulator, follow the link and use the code: LATEBLOOMERACTOR for 30% of your first monthly membership.

And finally, I am a huge advocate for and user of WeAudition - an online community for self-taping and auditions. Sign up with the PROMO code: LATEBLOOMER for 25% of your ongoing membership.

Good morning everyone. It's morning for me here in Australia. I'm David John Clark, the late bloom ragdoll, and welcome to season three. Yes, it's season three. We've made it this far. It's fantastic. I'm recording this episode in November 2023, because I do have a trip to the United States over Christmas, the new year, and this episode will be coming out just as I'm flying back from LA, I believe. So here we are, ready for season three with the wonderful John Orsik. John, welcome.

John Orcsik:Oh, nice to see you, David.

David John Clark:Thank you very much for agreeing to come on the show. It's an absolute pleasure to have you on board.

John Orcsik:Look, it's a pleasure, not a problem at all. I did a couple of these podcasts. I haven't been to America for about eight, nine years. And is it Aussies working? There's a group called Aussies or something over there. Australians in film. Yeah, that was it. I did a couple of sessions while I was there with them.

David John Clark:Awesome. Well, before we go in, I've got a bunch of questions about acting and training and etc. We're going to go back in time a little bit, because you have been in the industry for a while and I'll leave it up to you whether you say time frames or ages or anything. Can you just give our listeners a bit of an intro into who John Orsik is, where you came from, your background in acting and where you are today?

John Orcsik:Well.

John Orcsik:I actually span a much bigger arc than most people think, and I guess I come from Perth and I wasn't born in Perth. I was born in Austria but my parents were refugees, if you like, and went to. We were just dumped in Perth and all the rest of it. So my education was in Perth and I had always harboured this. I'm going to say notion, because that's what it is. People either want to be actors or they don't really want to be actors, and they find out that they really want to be actors, then they really work very hard. Those people who think they would like to be actors don't work that hard and then wonder why nothing happens. But yeah, so I grew up in Perth and there was no such thing. Then it was theatre. So my training was with an amateur theatre company there and I did a lot of plays with them into my I guess I started about 16, 17 years of age, into my teens and very early 20s, and then at one stage I was playing Biff Loeman in Death of a Salesman for their Salmon to the Theatre Company, which was a very good company, by the way. They were very high standard and the director of the Perth Playhouse then, which would be the equivalent of the Melbourne Theatre Company here In Melbourne or the Sydney Theatre Company. Anyway, he came, he saw the play and he came back stage to see me and asked me if I wanted to be a professional actor. And I said, yes, I do, that's what I'm doing all this for. And anyhow, he then gave me a role in his production of Henry IV, parts 1 and 2. And I had one line and I stuffed that up on a part nine. I thought, well, that's the end of that.

John Orcsik:That was a short-lived career, but anyway, I soon learned what not to do rather than what to do, and so I worked there for about two years and then decided look, it's time to go. You know, I'm 4,000, 5,000 kilometres away from the action, I guess. So I packed up and I came over to the Eastern States, as we used to call them over there, probably still do and then went to Sydney. I thought it had all happened at once. I mean my first job within three weeks of hitting Sydney, I auditioned for a play called the Knack and played the lead role opposite Jackie Weaver, who was then also a very young girl like me, and I didn't know who she was. She didn't know who I was. I mean, none of us were of any note at that time, but we just had a great time doing the play and we two were Tassie doing it. So I suddenly saw Tasmania, which I'd never seen before either, and it kind of went from there. I guess you know it's a very long story. David, you really want to hear this.

David John Clark:As much as you think it's permanent.

John Orcsik:I mean, it kind of goes from there to the end of that year. During that year I was one of the first well, I was the first actor to ever be in a couple of American plays that were never done here, never performed, and it was. It was quite amazing. Then I auditioned for the Melbourne Theatre Company at the end of that year, and I can tell you when that was, that was 1969. Wow, and I got in.

John Orcsik:So I spent the next two and a half years at the MTC as a contract actor and at the end of that time not me I was offered another season that each season ran for about five months. So my agent, who then was Faith Martin and then became Shanahan, eventually said I think you've done enough theater, it's time to come back to Sydney and do some film and television. It's the beginning of the film and TV stuff and it began in Little Things. I do remember one wonderful moment of being in theater and being and we'll talk about the acting thing as you wanted to later, but as we go on. But I was brought up or studied as much as possible the standard Stanislavski methods, blah, blah, blah. It never quite worked for me. It seemed to work against my own instincts somewhere. Rather. Anyhow, I sort of worked on this and tried, and then I remember I got a role.

John Orcsik:I had two lines on a series called the Link Men. I think it might have actually even been true here in Melbourne. Anyhow, there was not a very good series, it was a police series and there were a million police series going around in those days. Yes, to come. Yet beyond that was Corfinsworth or that four or five, culminating, I guess, in Copshop down the track, and I had two lines. I remember thinking I am this waiter and I had designs on this girl who was having dinner with her boyfriend and I'd made up this whole backstory. I did everything. I missed my cue about four times to go on and the director came back to me eventually. He's an English chap and he came down. He put his arm around me. He said my dear boy, just say the fucking line. I thought you know something. It's as simple as that.

David John Clark:I love that. I used to ask a question at the end of my podcast I don't do it anymore about what your t-shirt quote would be, and that could be your t-shirt quote Just say the fucking line, absolutely, just say the fucking line.

John Orcsik:I mean it's resonating now. I mean that was 1972. Wow, 1971. It was, and I still remember it, I'll never forget it. I mean I also thought, oh my God, that's the end of it, I'll never get another role again. And it then went on. And then I got another small part and another Crawford's production and another small part. And this is what was wonderful about Crawford as a company which doesn't exist today, particularly for young actors they gave you something, they tested you and they gave you something a little bit bigger. Then they gave you something a little bit bigger. Then they go look, this person can handle it. And after that I only played lead roles for them Wonderful. And then I also wrote for them. I wrote several episodes of DB4, matlock Police I think I wrote one homicide and Bluey. I wrote a couple of episodes of Bluey, which is another police series, and then I wrote four episodes of cop shop, eventually, in addition to acting in it. And I'll tell you how, isn't that?

David John Clark:interesting. I'm sorry I was just about to say that TV show called Bluey, and now we've got the cartoon. He's called Bluey, isn't he? Yeah, I wonder if they drew on that in any way.

John Orcsik:No, they didn't. I'll tell you, it was based on Bluey. Australian version was based on. We copied everything that happened overseas, particularly at that time. I mean homicide was a copy of, in a sense of, an American homicide police series. I mean, they all were Bluey.

John Orcsik:There was an actor and I can't remember his name. He was a big actor. He was a big guy who played a cop on an American series. It didn't last all that long, maybe two, three seasons, and Bluey was an actor here and I'm trying to remember his name. He was a lovely man. He's actually a comedian, a comic, a stand-up comic, and he was a similar stature to this American actor. So they simply started a show called Bluey.

John Orcsik:It didn't do that well and it didn't last that long. I think it went for two seasons. I think I acted in one episode or two, but I know I wrote one or two all those time ago. But that was kind of like. You know, I don't believe in any sense that you necessarily are stuck in one genre as in an actor only. I think it's a field that is used to express yourself in whatever you want, if you want to write and you think you can. Most people think they can't, but they actually can. And so writing and acting, I think, are synonymous with each other. As then comes directing. It's also part and parcel of the entire thing and there's no reason. Well, we can see today, you know, all major stars are also directors and they also write a lot, but it's made easier for them because they have the cloud to do it.

John Orcsik:In the days when I was doing it there was none of that. It had to be about how good was it that you were writing? But I at that time had a wonderful two or three years, because every time I came down for Crawford's to act in one of those police shows, they also hired me as a writer, because it wouldn't be an extra airfare. So I was down here on my day off as an actor. I went and had a writing meeting, a script meeting, and so then the next time I came down as a script writer for the edit, I was then given an acting job. So I always was getting two jobs at the same time. That lasted for about two or three years and then I left there and I did a whole bunch of other things.

John Orcsik:I worked a lot for the ABC in those days, ben Hall in particular. I played Flash, johnny Gilbert, in that series, which is a and that was quite a lot of fun, a massive production for the day. I believe that at the time each episode costs the same as an average feature film would cost to make here in Australia, which was, but today's standards it's a penny, it's nothing, but in those days it really was. So apart from Ben Hall, I also did another little series called Beyond the Break, which was about a surf, lifesaving and really, and another one which was fantastic was a one-off. It was a telly movie called Displaced Persons and directed by Geoffrey Nudge. That was really. That was really a very interesting telly movie in which I played the very opposite.

John Orcsik:See, up until that time I was playing tough guys, I was the cop. I mean, that's what cop shop eventually happened, and it happened for that very reason and I didn't care. People say, ah, you know typecasting, and I say, listen, as long as you're working, who cares? I'm trying, and there's no such thing as typecasting anyway, because you will only be cast as to how you are perceived, not by what you can do. It's your suitability that matters in a screen test, not your ability. Because you've been asked to screen test because everybody already assumes you have the ability. So that's kind of there.

John Orcsik:But that was about a group of people that had fled Europe just post 1945. And I was cast as a Hungarian Jewish scholar. Now that was so far away from the image it didn't matter, but then at the time I was the only and I had to speak Hungarian. Louis Narrow the late Louis Narrow, wrote the script. It was a very good screenplay and I was the only Hungarian speaking actor in the country, especially at that age. So they really had no choice, but I did.

David John Clark:Cornering the market.

John Orcsik:as I said, yeah, I did love it and it was terrific and it opened people's eyes. Oh God, you know, you just don't have to play somebody like you know tough guys and all that jazz. So you know, it kind of went on until I guess you could say cutting a long story short. You know there was theater happening in between as well. I did the odd play here and there and then the little movie here and there. So, look, I guess you could say Up until the end of cop shop. I was literally never out of work. That's fantastic. I was very lucky. If I wasn't writing, I was acting. If I wasn't acting, I was writing. The only thing I didn't delve into in those days which I'm now sorry that I didn't but, and that was I should have moved into directing as well, and I could easily have, because at Crawford's at that time all I would have had to have gone is gone down to see Hector and say, hey, I want to do some directing, and they would have made it happen.

David John Clark:So, that said, all those early days in acting, reflecting on those roles, so this will test the ages of my listeners here. So we've got homicide and Division four and Matlock leading into cop shop, as you've mentioned in 1978, playing detective Mike Giorgio.

John Orcsik:Yeah, that was it?

David John Clark:Yeah, which?

John Orcsik:was a story in a moment to, because that's very funny but gone.

David John Clark:Okay, definitely, that was a significant point you create, but all this, that learning as you're acting, and this will lead into your development of taffter, I'm sure, which we'll talk towards the end, totally so, how did these roles influence your understanding of the industry and and shape your approach to acting, especially considering the different nature of television?

John Orcsik:production. Well, massively in many ways, and not at first. At first I was kind of doing the same sort of thing, but it eventually made me develop a system Emotional expression that I teach, and have done so for nearly 20 years and have improved on it more and more and more and more. And people often say, oh, look, I can't get in touch with my emotions, can't do this, I can't do that. Well, my theory is you don't actually have to. There are things that you can do, and it happened because I was constantly under the pump to find a new way of doing it. Look, david, we did 90 odd episodes a year. One hour episodes, two hours a week. We were shot the equivalent of a telemovie a week. Wow. And so the pressure on you as an actor is twofold. One is sit back, take the money, relax, just do the same thing you do every week and it's fine. Everyone loves you, you've established this, you've established that, and just roll on and let the money roll in. Well, never really rolled in in those days, but anyhow, the other thing is you challenge yourself as an actor.

John Orcsik:As a group, we challenged ourselves in that cast, ran some workshops on occasions on a Saturday, and we chose to do Shakespeare and we chose to do the very opposite of what we were doing, so that it would stretch us as actors and we would discover things about each other that we hadn't known before, that we hadn't explored before. But also it was an exploration of how can I do something more efficiently, how can I do it better, how can I do it more convincingly? How can I do? All those questions were to eventually shape tafta. But they go back to those days where look, where you are there five days a week. You are there from dawn till dusk and sometimes late into the night. You are working on a series television in those days in particular, something like that.

John Orcsik:You wouldn't do it today. Today you would treat an hour a week, not two. You would get X number of times. It would be just so many. I just think it's so easy today, so easy Basically, comparatively, only because of the schedules, the work you were expected to come up with and at the same time, as a group. I must say that cop shop group, we were all the best of friends and stay best of friends, and we still are best of friends for those of us who are still here. We literally lived in each other's pockets, and that was a development. That was also interesting, because normally when you work together with a group great, we're with a bunch of people for a long time you think, oh, I'm going to get the weekend off, but no, on a weekend someone would say, just like, I'm having a Barbie on Sunday, you want to come over and we go, yeah shit yeah we're there, so we're all there.

John Orcsik:So we were there Sunday, and then we were there Monday, bloody morning, you know and that happened with monotonous regularity. We even intermarried in the show. We still married. The continuity girl then became a casting director and I married Paula. It was just happening all over the place.

David John Clark:It shows the difference in the industry size, wouldn't it? Compared to today?

John Orcsik:Very much so. But I mean, I just think the size today is scattered. Look, and this is not a bitter pill or any other nonsense, but I look at shows that are coming out today and I'm not talking as an old man, which I am now, but I don't think I am, no, do I behave like that. But I think, despite the naivety of the writing in those shows, they were not pretentious. I find that today's shows are pretentious. We write for a reason. We must have a social agenda of some kind and we worry about the social agenda more than we worry about the story. We've lost the art, in my opinion, of storytelling. That's a shame, isn't it? That's, I mean, I could be wrong, but not from what I have seen, very rarely does something come up that I think, gee, that's really good. But you know, let me tell you the story about how I got into culture. Yes, definitely, that's really quite amusing.

John Orcsik:I was brought down to Melbourne in secrecy to audition for this show called Cop Shop, which I thought was a terrible title, and I thought, oh, it's just so, never will. Anyway, I came down and went into Channel 7 and there I was, did my audition and left, Flew back to Sydney because I've seen it again. As to me, my Tony Bonner, who wasn't late at the time but became later I mean Tony also auditioned for the role. Tony got the gig for this particular character Anyhow. I thought, oh well, that's it. I had two other offers on the burn at the time. I had another soap and I can't remember the name of it Young, something or Other, and also the ABC were doing a thing called I think it was the ABC, I'm not sure now called Chopper Squad, where I had played a guest role in a surf lifesaving captain. It lost the use of his legs because of mental thing, but at the end of the episode he says I got more and I got more. That's the story right for you. Anyway, talk about cliche. And then.

John Orcsik:But they offered me the next season and I thought, oh look, I could spend 26 episodes jumping in and out of helicopters on the beaches in the summer in Sydney. That sounds like a lot of fun. And I was about to agree to that series when Crawford's reign my agent, the great Bill Shanahan at the time I said we really want John in the show, that show, that role that he auditioned for with Tony. That was terrific, but Tony is more right for the role. But also that role won't really have longevity and Tony doesn't want to do it for that long anyway. But we really want John in the show and we want a different kind of a character.

John Orcsik:And they said how many languages can John speak? Because we want him to play a multilingual cop, so we will use the use of those languages. Now, that was going to be a first and I said at that time I think I could speak four languages quite fluently. Still, it's all gone now. Well, I mean, when you're a migrant kid and you come there and you're in a refugee camp and there are all kinds of different nationalities there, and you're a kid five, six, seven years of age, you pick it up and it takes absolutely nothing. The communication was easy. I mean, the only language I couldn't speak when I came to Australia was English. But I soon made that happen. And then he wrote back and said yes, it's going to be four languages. He reckons he could do Get away with a couple of others. But they said oh, terrific, well, that's what we want him to do.

John Orcsik:Now Bill, who was a very smart man, turned around to them and said look guys. That's terrific, but this is a special skill. You're not going to find another actor in the country who can do this. And so, apart from the standard fee, which we're going to talk about in a minute, I'm also going to charge you $100 per language per week, whether or not he speaks those languages or not. That's a standard add-on. And they went oh right, we'll get back to you.

John Orcsik:They rang back the following day and said can John speak Greek? Bill said well, it wasn't on the list, but I'll ask him. So he rang me and I said no, mate, I mean, I would have told you if I didn't know I can't speak Greek. So he rang back and he said no, no, he doesn't speak Greek. And now later they rang back again and said we want him to play a Greek cop. Oh, no See, it was about the money. They didn't want to pay the extra, they didn't want to pay the extra bucks, and that was really hysterical.

John Orcsik:And but at that time, as a student officer and actor and I talked about it with him, I remember with Bill I said I'm not going to speak any Greek on the show. I said people can speak Greek to me, but I will be going back in English. The reason is, david, that once you set up something, you can break the mold, and if I've set myself up as X, I open my mouth to speak. Melbourne has the second biggest Greek population outside of Athens. I believe, or did have, and they'll say that boy Hino-Greek. Because my accent, I will not be speaking properly, so I would rather say I'm Greek but not speaking. I might say yes or I might say the odd word, but that would be it. But the fact is that the entire nation believed I was Greek.

David John Clark:And in many ways it's still do.

John Orcsik:That's what I mean. So you've got to go and they said, oh, you're doing it because you got pissed off about the money. I said no, no, no, you don't have to say that, I wouldn't do that, that was something we. You change your mind? No, because if I was that pissed off I'd say no, stick to the show where you want that best. I don't like the title. How wrong was everybody? I think there was a headline in the Sydney paper at one stage when it first came out, saying what a load of cop. This later crap or something. Well, six years later, rating killer later. I mean it was amazing. But there was an amazing show for that. But you know, I mean prior to that, prior to pop shop, I mean I was doing number 96. I was in the show there for a month or two and then I did the movie.

David John Clark:And number 96 was just such a big change for Australian TV. It wasn't a tested boundaries that had ever been tested before.

John Orcsik:And well, exactly, in a very sort of daring way, for the times we don't do that anymore. We don't do that. That's what I'm talking about today. We're so super safe for a bunch of boring, dull wokes Well, I'm not, but that's what's happening out there. So the material that's coming out is like that, you know it's. You can't have that because you've got to have one of those in it and one of those in it, one of them or one of them. Well, what's the story about? We go back to what is my story, and to me, that's what writing is about. Story, it's not about making it. If the story makes a social comment, great, and if that's it. But tell the story. But yeah, I mean cop, not chop, not cop Number 96,. I mean then I had the distinction of having the first male kiss on Australian television was Joe Hashem. That was very funny. I didn't know that. Oh, you know that Joe and I killed ourselves laughing. That was in the movie.

David John Clark:And was that done? Was that done in a comedic way, or was it no?

John Orcsik:no, oh, no, it was real. Oh, it's real. That's another very funny story. I was down here in Melbourne and I was shooting a film with Tom Thompson called Peterson and Jackie and a bunch of other guys and I've never huge role in that, but it was. It was a lot of fun.

John Orcsik:And Faith Martin, who was my agent at that time, just before Bill took over the agents, sent me down the script of the number 96 movie, saying they wanted to play the same character that you played in the series. Well, the guy that I played in the series was a bit of a. You were the big ladies man. I mean in the fair with the lame Lee and the fair with some cup to three of the ladies show. I Read the script and this guy's gay. I sent back the script To faith that I said no, tell Bill Harman I'm not doing this. This is not my character. Money idiot I was anyway. The attitude was ridiculous. Anyway, then Bill came back, being in New York, to that bill wasn't what he wants? More money, is that what it is? I don't think it was for money. I just don't think he likes it. I don't give us to do it, this is what. So anyway. Eventually he kept at it and at it, and at it and at it and I had a very good friend who was part of the show at that time. It was one of the producers called Bob Hugh, and Bob said off, a Christ sake, john, it was also an American, will you see him? So I said okay.

John Orcsik:So it was after I finished Peterson I went back and I had a meeting with Bill and I said, bill, I Was playing this wild guy. You know, this guy is sort of off with every woman in the bloody place, and now he wanted to turn this character gay. He turned around to me Absolutely with complete open-minded. So, john, everything changes. Wow. In the end I went bugger, okay, what the hell? And, and. And. It turned out to be one of the best things I've ever done when I say best things in terms of, I guess, notoriety, but it was also a lot of fun and I worked with people that I really liked. Again, the Joe was a great guy. I think Channel 7. Twice I was on a show there they had called when are they now? Some years ago, and the second time around they actually flew Joe out of Jakarta, because Joe lives in Jakarta these days, I believe. So they're uniting us back again on which was, which was a lot of fun.

David John Clark:And what year was that on television, when you played the, the gay character?

John Orcsik:Well, it was in the movies, first the movie sorry, yeah, and then it went to television some time after that. I'm just trying to think must have been late. My mid 60s, 64, 65.

David John Clark:So very much in a time when homosexuality wasn't portrayed in TV I don't know my time frames when Sydney started kicking off with the you know the game Artigraha and making and people coming out and trying to Understand and culture changing so that sort of leads into. We were talking about it before, about the diversity of television and that. So we've.

John Orcsik:But you know the beauty, I'll urge this. No, no, we did, we did and I I'm totally for it. The thing about it was that I think we did it Because we wanted to do it, we found it interesting, we found it entertaining. We didn't do it because we socially felt we must. Okay, which is the difference between then and now, in that sense, nobody cared. Nobody cared.

John Orcsik:I mean, I must say most of my friends were going anyway. They were in the theater and not in the theater, film and television not so much, but I mean nevertheless, and and they were all my, my dear good friends, I mean nobody cared. I mean Susie myself, she was a friend of mine, she was also my agent, she was a casting director. One says dear. Or Susie passed away a couple of years ago, but we used to get up to cansellers and hire a bit there and have lunch and watch the game Artigraha from up there and it was. It was a lot of fun and it was terrific. And I just think that sort of some kind of a criminius crept in for whatever reason, I Don't know.

David John Clark:Well, see, I think there's a streaming service now, I won't know your names, but there's a streaming service that Won't take on productions unless you tick all the diversity boxes, and it's got to literally have every single To get a right story around that. I mean, that's. That's like saying Dunkirk, for example, when the movie Dunkirk come out. There was a question there why there were no women in the movie. No well, hang on a second. So it's a. It's a movie about soldiers in World War two, you know exactly.

John Orcsik:I mean the women were not in the field at that time. No, I mean they may be today.

David John Clark:But exactly, and if you wrote a story today, then you've got that ability to put the diversity in there. Diversity Stories should reflect exactly what they are. But, like you said, we're now writing stories to tick 200 boxes, which well, we're not writing stories anymore.

John Orcsik:I think what we're doing is writing, is ticking boxes and hoping there's a story in there. I mean it's everywhere, I mean it's it's not just Australia, but Australia in particular, just. And people say, albert, this is our story. No, it's not our story at all and you know it's. To me it's a bit of a pity. Look, we'll get through it.

John Orcsik:The pendulum swings, david. It swings this way and it swings back that way and it will do so forever. And I've seen it. I've seen it go from the extremes of the 60s and 70s which are amazing, fun too. What was in the early 80s? Then it became more and more restrictive. And I know, on cop shop we there were certain things we could do, because it was an 830 show, but at a 730 show we couldn't do the things that we did at 830, whereas, of course, today, being a streaming service doesn't really matter. I mean, you can, you can tune into anything you want at any time. You know so, but but you know I ended up. I ended up, I guess, forming taffta With Paula, curiously enough, way back in 19. No, yes, 94.

John Orcsik:That sounds right, paula and I sort of split up is a funny story. Paula and I sort of split up and both living in Sydney and I was working for an acting school there, teaching and Working. I think I just finished up a little stint on home and away and various other things and and she rang me and said I've just been offered a 12 month contract in Queensland for a show called Paradise Beach. And I said oh good, good on you. We were funny enough, we were still friends, which is weird. But anyway, we were and still are very, very friends and that's that's the way to do it is what life's too short, my friend accurate.

John Orcsik:After many years of waste of time, I so she went off with Jessica just feels about eight years of age at the time and I was an LA directing and doing her own thing, which is wonderful and she's just had a baby. I've just become a grandfather.

David John Clark:I'll come got you guys.

John Orcsik:He's been wonderful. And so she's gone for about two weeks, three weeks maybe, and my phone rings as my agent who is by then someone else, bill had died. I'm gone and I was no longer with that agency anyway. It was John can and they rang me and said Do you want to hear the good news of the bad news? I said I'll stuff the bad news. That's the good news. He said well, the good news is that Paradise Beach productions have asked if you'd be interested in going up there for about three months as a guest On the show. I went on great, yes, love it, that'd be fantastic. I suggest you know all the rest of it. And so I Said oh, it almost doesn't attend to myself. What's the bad news? You said I want you to play Paula's love interest.

David John Clark:So it's a bit like Crawford's, did she know?

John Orcsik:that I rang her and said so we had a big laugh about it. Anyway, I went up there, I, I, I did Show there for a while and then later on I was in another show there. I think we just stayed up there for about four or five years and, and in the January of that year the producers of the show, who were both ex-Crawford's people, said look, we're here, you've been doing some teaching. Can you do some teaching up here? Because we are literally hiring 50 worders and flying them up from Sydney because all the guys around here are so theater bound, it's a pain in the neck. So that's how we started. By then, as straight whatever, I got back together again and Tafta was born. Literally then that was 13 years ago, this coming January.

David John Clark:I talk about a lot of my podcast about sliding doors and how certain doors open when you just don't expect them. And things have to happen today because of that.

John Orcsik:I mean I was still doing a lot of acting then and all kinds of different shows, not just up there. I did a couple of movies up there and then I did another ABC show which I flew down here to Melbourne for was a kid's show, I can't remember what it was called, but it was interesting, as I say it was. Even then we were concerned with the story, not who was in your story, was that the one about the zoo? But it was yeah, so it was tough. Then we opened Sydney and then we opened Melbourne and then we had three, and then it's again a bit too hard and the times are tough at the moment.

John Orcsik:Maybe he's got any money, which of course is interesting Well, or if they do this, I can't spend it. I'm not risking it, but that's okay, we'll get through this. We always have all kinds of things will happen. But I mean I've had a very interesting I'm finished yet either the way career. While I was there actually doing that, I wrote and directed a telly movie called Academy which channeled mine board, and that was sort of when I started to really delve into the directing part of it, which I quite liked, and I'm messing around with that still at the minute, which is fun. But yeah, it goes on, david. I mean we could be here for a while.

David John Clark:It's a it's brilliant to talk to you because I've told my wife I was interviewing today and she's loved all the iconic TV shows and she just can't believe that we'll be sitting here having this chat about iconic Australian history.

John Orcsik:Well, it's just brilliant. It is very true. Look, I mean, I can tell you now that I did. I did a God. How many days of interviews for the, for the archives in Canberra a couple of years ago Wonderful, and it took several days and I thought, Jesus, I didn't think I had done that much until I started to talk about that stuff. But we have. I think we have a possibility of a very new and vibrant industry. I think we've gone global and maybe this is a transition as well, and we are in a transitory period like that. So we're not quite sure we want to hang on to our own roots, but we are also looking global at the same time. So what is it that have to do? Yeah, so what is it that we have can translate into that big picture and not just stay within the small picture?

David John Clark:Well, I think it was good, because I think those stories are stories to store on as that's cool, and bringing that, tying that into tafftor, and what your goals are as a training organization. How does tafftor operate in this market? What's your goals with training actors as opposed to a standard drama school that offer the three year degrees? You branch out with a lot of different casting director workshops. I'd like to quickly touch on your training method as well. That sort of stuff.

John Orcsik:I mean, look, what we do is different to what everyone else does. In the first instance, I have ditched all those mysnerian, chicovian and all those based theories on acting, all that stuff about getting into yourself and finding an emotional recall, which is nonsensical because it does exist. What I did do exist. Find out. That's quite ironic, but through my because. Then I began to study the whole emotions thing. There's actually emotions molecules that exist in your body and they are real and they cluster, if you like, around certain organs and certain stimuli happen. It's too long a story for us to go into, but that is the basis of it. And there was a wonderful woman, professor Candace C A N D A C Hall, who actually was able to measure the opiate perceptor, which is as well as this part of the molecule of emotion, and therefore proved that this isn't just a feeling, but this feeling is in fact a physical reality. Now what we need to do is evoke those physical realities and then we'll find it so much simpler to tap into those so-called emotions. So I have a system in which I do that.

John Orcsik:I also think that acting is simple. We don't need three years. Look, at the end of the day, someone says okay, david, I really would like to see you in this. There's the script. Learn the lines and come back tomorrow and let's see how you go. Acting is about shown. It's called showing. You can have 25,000 certificates, you can have a doctorate. It's not going to make you a better actor. It might make you an interesting academic, but it's not going to make you a better actor. Acting is very simple. If you can't learn everything you need to know in six months, then go somewhere else. The difference is that all those other institutions you then get the chance to practice for a lot longer before you let out into the industry.

David John Clark:Yeah, because my son just finished year 12 and he's applying for Flinders drama for the three-year degree. But he's 17 years of age and you can't go wrong purely on that experience level.

John Orcsik:Yeah, see, 17 years of age, though today, unlike in the Cops Club days in that era, if you like, there are shows for all those people. They're not just token gestures. I did a series called Zoo Family, which was wonderful, but that was a token gesture by Channel 9. At the time they bought 26 episodes because they had to make up their C classification. Today we don't care about C classification anymore because that showed, although written for kids can suddenly become global. Now it's a money making entity, whereas at that time it was a gesture. I mean, we used to fight so hard to get kids drama up, I remember, but that isn't there anymore At 17,. I mean, you know, this is what I point out to them.

John Orcsik:At one stage, all your standard institutions didn't take anyone much under 20, 21 years of age because they wanted them to have a little life. Well, the problem is that I've got a bunch of students, for example, who have been with me since they were 14 years of age, our teenagers and our teens. They are now 18. They don't need to go to a three year institution. They need now exposure and work, and they're the two things that at the time matters. You know, work, work without this. You know what they're doing. Work with the directors is just a fucking line.

David John Clark:It's interesting. I mean Codd has been. He's been doing classes for a couple of years with his agency here and been making his own film with a bunch of people. We watch him on screen, he's that's what you need to do. It's one of those things, because if he gets a call to go to home and away tomorrow, then he might not need to. I've heard of people who've dropped out of the uni because they were on home and away, and it becomes their university Absolutely.

John Orcsik:Look, there is no going way back to when I was 17, 18 years of age and just in school I auditioned for Mida. At that time, that time was only a two year course and you didn't get any kind of government assistance. There were no student loans. You had to pay for it. It was straight out. You want to do that and I can't remember what it cost, but it wasn't cheap by any stretch of the imagination.

John Orcsik:Now I was in Perth and they auditioned all over the country which is what they do still and which is fair enough and I got accepted to go to United and I went wow, okay, South or well, dad's going to have to pay, I don't have any money, et cetera. Well, my dad was okay, it was reasonably well off. He came, as other people did, to Australia and, not being able to speak English, and ended up being a builder. He was actually an architect but ended up being a builder and building schools and building all kinds of stuff and doing okay. But as life luck, whatever else would have it, he suddenly fell ill and he had cancer. So I then wrote back to my current memory exactly who they were at night and said look, I'm sorry but I can't come over. My dad's just been diagnosed with cancer, et cetera. And they were lovely. They wrote back to me and said look, John, we understand, we'll keep the position open for you for next year. You don't have to audition again, We'll just accept you, in other words, and I went wow, that's really, really nice.

John Orcsik:And then, of course, as life happened in that towards the end of that 12 months, my dad died and it was time for me to go, and by now, of course, he was going to be short and mum couldn't do it. I couldn't leave her. So I wrote back to them and said I'm sorry but I can't go, and pointed out the reasons why. And they then beautifully wrote back and said if you can see your way over here, we will give you the microchilispe scholarship to come over. But I couldn't do it, it was just not possible.

John Orcsik:And it was at that time that I started then to do some really serious roles with this major amateur theater company. And then came the Playhouse, the director and me working there then for the next two years. By the time I finished working with professionals for two years, I said to myself is there any point in going to a drama school. The answer was no, there wasn't, Because I learned more from those guys than I could ever learn in two years. It would have been a wonderful time, I'm sure, and I believe this is a great deal of camaraderie.

John Orcsik:And John Clark, who was head of MITRE for a long time, wasn't at the time a bit later was a friend of mine. He came to see most shows that I saw and in fact he did some workshops Shakespeare workshops for us at Tafta Incident a couple of times, which was really nice. But sometimes life has its own weird and wonderful way of shaping your future and saying what if I had done this or not done that? There's no point to any of that or thinking about it. But at the time that's what happened and they were my decisions and they were things that I had to do. Okay, it made it a bit tougher down the track, but then again, I've never been anyone to shirk something. That's tough, maybe because it's how we were forged, in the words of the great Bard.

David John Clark:Wonderful, awesome. I'm mindful of the time.

John Orcsik:That's okay, mate, no problem.

David John Clark:That's on the training front that we were talking about. Yeah, you're discussing not being able to go to drama school or going to drama school. Me being a late bloomer actor, having started acting in my 40s One of my biggest things I get I try to get as much training as I can, but I've done courses with you and I've done the casting director workshops but it's finding that believability. One of my biggest statements that I've got, which is why I haven't landed the 50 worders or the 20 worders, is my auditions, so to speak, lacking the believability of character. So, from your perspective, with all your experience in TV and film and now as a teacher with Tafta, where can we get that from? How do we develop that ability to come on screen whether it's on set or whether it's in an audition, and have that believability of character? So someone goes I'm not watching David Clark. I'm watching David Clark, the actor, whatever character I'm playing.

John Orcsik:Now you notice I smiled at that. The fact is that we're always watching David Clark, and the more David Clark thinks he wants to be someone else, the less successful he's going to be at that, if that makes sense to you, is he? I am also writing a book it's probably about three quarters there at the moment and I have a chapter on just the very thing that you said is character. Where that? Who am I? Where have I come from? What do I do? I throw all that out the window.

John Orcsik:To me, character is about detailed behavior and the believability is really something that can only come from you. You have to stop worrying about who you are. It's David Clark delivering the lines and the moment with the truth as David feels it not sees it, but feels it. Once you do that, you've got character. I'm going to tell you a quick story about that fairly recent. The last three or four years I did an episode of Dr Blake's Motor Mysteries and I had auditioned for the show a couple of times and was unsuccessful On this particular time. I went in there and Lou Mitchell was the cast a wonderful lady I've known for many, many years and the character was a gypsy leader of a Gypsy band. His daughter was murdered and he obviously is a suspect.

John Orcsik:And the scene was him discussing with the Doctor Black character, his daughter and his emotional. So he had to be crying or near crying or apparently crying or dying. And at the same time I said can you give us a mede-European, hungarian, transylvanian, romanian accent? So I said yeah. I said yeah, I can do that. So I said I remember saying my dear Doctor, you have no idea what you are talking about. Anyhow, I did all that and did the tears and all that and left.

John Orcsik:And then I was on my way home when my phone rang and it was the director. It was going to direct it and I remember Ian rang me and said can I talk to you? And I said only if you've cast me. I said joke. And he said well, of course I have. Why am I fucking calling you? And we had worked together on the ABC, god knows way back 40 odd years ago. He was then an editor and he was editing all those shows that I was talking about back there in the ABC and he was a director, lovely, lovely man. And he said how do you feel about long hair? And this is how we put it how do you feel about long hair. I said what do you mean? How do I feel about long hair? I said I don't have the hair I had when I was in cop shop. He said no, no, no I know that.

John Orcsik:I said but? And I said I'm not going to be able to grow it because we're shooting. In what? Six weeks? He said yeah. He said but don't worry, but how do you feel about it? I said you want? I said what you're really saying to me and is that you want me to have long hair. Is that right? Or you would like me to have long hair? You would like me to consider that? He said well, yes. I said fine, I don't mind, that's cool. I said I haven't even thought about this, but let's say cool. He said good, good, good, thank you, hang up.

John Orcsik:And my phone rang again in the car just before I got home and he said how do you feel about a beard? And I said six weeks. I said I can grow you something in six weeks and I'm going to be massive. He was about that length. I said but I can grow you something in six weeks. I said you want me to have a beard? And he said that would be nice, do you mind? I said no, I don't mind, it's great.

John Orcsik:I got home, I was inside, I wasn't there long and my phone rang again and it was the end again and I said we got to stop meeting like this, right? And he said how do you feel about long fingernails? Oh, my God, I said what he said. How do you feel about long fingernails? I said I don't care why you want me to have long fingernails. He said yes, I think that would be fantastic. I said all right, I haven't even thought about this. All I've done is cried and given you a bloody accident. And now we're doing all this. And he said I said why do you want me to have long fingernails? He said well, I've got this shot in mind because you will be a suspect, because on that show everybody was a suspect. Obviously it was a who done it. And I said yes. He said I've got this shot in mind where I want to shoot past your hand, which is holding a walking stick, to the police who are talking to you, and I just think I'd like to see those talons as I shoot past your hand.

John Orcsik:I said what you're fucking saying is you want me to have a walking stick as well? He said oh, do you mind? And that was always a do you mind? And I said no. I said you know how much work you've just saved me? I said I had no idea what I was going to do, but now you have given me a character image. Do you see what I'm saying here? Suddenly, the outside went on and there it was. All I now have to do was deliver the accent and the emotions where necessary, and it's like instant character. And I know you can say well, how about a business? How about that? The same thing applies.

John Orcsik:The fact is, you can never get away from you, and that's one of the biggest mistakes actors make. They think I'm playing someone else. No, you're not. If you were really playing someone else, there'd be a whole bunch of white coded people coming to take you away because you'll be a menace of society. You can only ever play you with the emotions that you see fit, not necessarily the emotions as written by the writer, because that's the writer's emotions. When this happens to you or you go through this situation, I don't do, and never have done, so called script analysis. That comes later. What I do is I attach an emotion to the scene and to the character and I rehearse it with that emotion. Then I attach another. There are five basic emotions. We don't have time to go into that at the moment. Six perhaps actually.

David John Clark:Can people can buy the book.

John Orcsik:Yes, they will. There's an entire chapter devoted to it, which has already been written. It's about 15 pages, but examining all those things. But once you've attached these emotions to the scene and to both the characters, put it down and go away. Come back 24 hours later and see what has happened in your subconscious, see where now your impulses and your instincts point you to. Now you can rationalize. Now you can say yes, that really works, that works. No, that doesn't work all that well, but this does. Now I can put together the performance. But we tend to do it the other way around. We try and put together the performance before we've actually done the performance. That's the basics of my approach and I don't think that any of that particularly emotional recall where am I going to get this from? Truth in performance, oh my God, truth in performance. I'm sorry, those things always drive me bananas and they are so old fashioned, they belong to a theatrical era of the 1930s that has stayed with us forever and a day. And because the teachers have stayed with us, and then one after another, after another, and yeah, I'm not going to go into it, but I mean it's just because people do what they want to do If they want to teach that, they can teach that. If people want to learn that, they can.

John Orcsik:I abhor my students or my actors writing on their scripts. Why do you want to write on the scripts? The dialogue is there. The first thing I do is I will read the script and I will read the script a couple of times so I kind of have an idea of I am interested in. Do I have a story in my head and what is the sequence of events in the story? And then I'll go scene by scene by scene by scene and in each scene. I'm not going to work out all those. Who am I as a? What am I as? Where am I feeling? It's no substitution, none of that stuff.

John Orcsik:And I'll tell you who taught me this. It was not I wish I was say, it was my idea that it's not. It was the wonderful George Melody who I worked with for quite a few years, one time another and George and I became friends Again. George has said you no longer with us With cop shop. It was that hard, the pressure was hard.

John Orcsik:I had to learn so many lines and I'd never done that before on a constant basis, week in, week out, and I was going to leave the show, I said no, I can't handle this. So George asked me to go to his place and I said I can't come over. Anyway, I've got too much to do. He said come over and he taught me how this can happen and work, and without me losing it or anything else. I said you get all the scripts six weeks in advance. I said yep. He said good, read them all twice. Take a day out on a Sunday to read them all. Don't do anything else, just read them. And he said then look at what you're going to do next week. He said once you've read them and read all the scripts, you now have a story in your head. You know what your story is for the next six weeks. I said yep.

John Orcsik:And he said then now, then go back and read what next week's episode is that you're going to be shooting. So I do this and read that. Read, never learn. I don't learn lines, never learn. Read. And I read them through.

John Orcsik:He said now pull out your scenes and put them in chronological order. You're not going to be shooting in chronological order, because that's not going to happen. Scene one you may shoot on Friday and not on Monday. He said but chronological order matters, because you again will have this week's story in your head. You know what you're going to be doing. Now read them scene after scene after scene. Now put all that away. And I said yep, and now learn the lines. He says no, now you know the lines, and he's right. I pull out the scene for tomorrow that I'm doing, or two or three, and look at them, one at a time only, and I know what I've read. I've read it now so many times. Oh yeah, that's what I'm doing and I know what I'm saying. I've applied some emotional detail to all those things. I don't have to go to the trouble of going. Now tell me, where are we on the night of the fourth? It's already there. Now I've just got to apply myself and attach myself.

John Orcsik:Mike Giorgio was me in many ways. I'm not Greek, but I'm not Australian, I'm European. I was a martial artist. Mike Giorgio was a martial artist. I was this, I was that. There were so many things that belong to Mike, that belong to me and in all other characters that I've played, and so does everybody else. They belong to you and that you make them belong to you. You do the study. I go well, I'm playing, I'm playing, I'm playing a doctor, I'm playing a physician, I'm a physician, I'm playing there. And again you go back to what are the physical things that I have to do physically and then the rest will just come to you. You can never get away from David. This is what I'm saying. As an actor, I can't get away from me. I can get dressed in a million kind of different outfits, but I can never get away from me. And as long as I don't try and become that nonsense, I will still be that. You will still believe me as that character. Do you understand what I'm saying?

David John Clark:Yeah, I do. I'm taking so much away from this. It's fantastic, it's. You know, we get into our heads so much, and there's especially with the internet, and there's so many courses, there's so many books, there's so many people yelling and screaming at you do this, do it my way, learn from this. You have to. This is how you do it write on your script, and I need to go back to where I was, where I started. I started on a very similar approach with you. I've never written on my scripts. I learned a lot of my beliefs from Jeff Seymour.

John Orcsik:Jeff is a great guy and his book is a very good book. I don't agree with everything, but nor should I but, and nor do you agree with everything I would have written. But but yes, it's a very good book and it makes terrific sense. The Real Love Act is a very good book. I recommend it highly.

David John Clark:And I think, just everything that you've just said in the last couple of minutes, I'm going to go back and listen to it myself, and everyone listening to the podcast should really just dive down into it, because I think there's so much in that I recommend I recommend two other books to you, david, just see if I can see them there very quickly.

John Orcsik:One is called how to Stop Acting. It's a wonderful book, and the other is the Science of Onscreen Acting. I think, and just can you excuse me for two secs Certainly, certainly. Yep, I recommend four books really, and Jeff's is one of them. The other one is Harold Guskin's book how to Stop Acting.

David John Clark:I have seen that one. I don't have it myself, but I have seen that one.

John Orcsik:And the other one a little more complex, but this one, the Science of Onscreen Acting, by Andrea Morris. This is a fantastic book, absolutely brilliant. Okay, that's a new one. And I also think, combined with all that, everybody, but everybody, should read the writer's journey.

David John Clark:I have heard of that one. I've heard it's a very, very good book.

John Orcsik:It is not just for writers, but it's also for actors. What it makes you understand is what's important is not who you're playing, but what your function is. What's your function in the story Once you can nail that down? Or what is your function at any one particular point? Not who you are. What is your function?

John Orcsik:My function in this scene is to give you the shits. For example, not because I'm a bad person, not because I'm going to be an ugly guy, not because I'm going to be bad. But they said no. My function here in this scene is to frighten you. That's it. It's that simple. So I will play the scene without in mind Nothing else. Or my function here is to lure you into something. Function is almost more important, because the character won't change. You are the character. You can't change the story. Look, the story starts here and finishes there. That's the story. You can't change that. The author has written the story. How you tell the story is up to you, and each actor will tell the story differently, but it'll be the same story. That's what's important. Love it.

David John Clark:Beautiful David. Thank you very much.

John Orcsik:I think so Anytime mate.

David John Clark:Thank you very much. Is there anything you want to end the show with? Anything you want to say to my guests?

John Orcsik:Well, if they're here, I mean you know, hop onto our website and have a look. Basically, that's what I'm saying Look at our website. We have got a course that is going to be beginning in early February next year and it's 30 weeks, three 10 weeks semesters, three full days a week, and we guarantee you will have an agent at the end of it and, in fact, probably in the beginning. But you will learn more. As someone said and I believe it's true and I'm not pumping myself up or anything someone came and said to me I learned more here in the week than I did in the entire two years. I did someone else, wow.

David John Clark:I mean, everything I've done with Taft has always been brilliant, and I've sat in a room with you yourself as you know so I always walk away.

John Orcsik:Well, david, you know, I think that the more you also begin to realise that acting is simple, it's child's play. And when I say child's play, because that's what children do. They don't ask questions, they don't get in their heads, they tell the story as they feel it and they see it and they move on and they can go from one emotion to the next and not worry about where did that come from?

John Orcsik:How did I get that? Oh my God, that's us. Once you're in your head, it's very hard to get out of it, and that's the whole point about everything. And that's the trouble with all the other complexities. It's not complex. Acting is simple. You know, and don't worry. In the scene that I'm doing now with you, I'm not going to care what happened four scenes ago. I'm only focusing on this scene, right now at this moment, this is the only moment that matters.

John Orcsik:The moments that happened to make this happen. Oh my God, you wouldn't think about that. Why? That's the story. You're the writer or the director. Now, the director has to think about all those things, right, of course, but not you. Your simple job is to deliver you, here and now, with something that you feel, not see, not think about, not articulate, but something that you sometimes can't articulate. And something just happens, as you'll find, with Harold Guskin in that book, and he says just try and do it differently.

John Orcsik:I had a very good friend of mine, who sadly is no longer with us in LA, and he used to rehearse his people and say I just want you to do all the cartoon voices you can think of with this scene. I don't want you to do anything else, just all the cartoon voices. Focus on those. And everyone did On the focusing of those. They then suddenly knew the lines. They absorbed a whole bunch of stuff that they didn't even know Subliminally. You know that happened, yes. And then you produce it, take after take after take, but each take is slightly different anyway. No two takes are ever the same, I think I'm sure. Thank you, david.

David John Clark:Thank you, and just quickly, john, when's the book due? Do you have a title on it yet?

John Orcsik:Yeah, yeah, I'm at the moment. I'm writing a sitcom at the moment because I'm doing a course starting in January. Well, it's comedy capers too. The first one was on sketch comedy and this is a course in SIDCOM that I'm writing the sitcom for the course. So be fun. Thank you, David.

David John Clark:Wonderful. All right, John.

John Orcsik:Thank you very much.

David John Clark:It's been an absolute pleasure and, ladies and gentlemen, you can check John out at taftacomau.

John Orcsik:Thanks a lot.

David John Clark:Thank you very much.

John Orcsik:Yes, you're welcome. See you later, thanks.

David John Clark:Thank you.

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.

The Real Life Actor

Jeff Seymour

Audrey Helps Actors Podcast

Audrey Moore

Tipsy Casting

Jessica Sherman and Jenn Presser

Castability: The Podcast

The Castability App

Wendy Alane Wright's Secrets of a Hollywood Talent Manager Podcast

Wendy Alane Wright

Think Bigger Actors Podcast

DaJuan Johnson

ACTORS! YOU ARE ENOUGH!!

Amy Lyndon

Act Bold - Where Talent Meets A Plan

Act Bold with Anne Alexander-Sieder

An Actor Survives

Emily McKnight

Podnews Weekly Review

James Cridland and Sam Sethi

Buzzcast

Buzzsprout

Box Angeles (for Actors)

Mike 'Box' Elder

Brian Breaks Character

Brian Patacca

Celebrity Catch Up: Life After That Thing I Did

Genevieve HassanCinema Australia

Cinema Australia

Don't Be So Dramatic

Rachel BakerEquity Foundation Podcast

Equity Foundation PodcastIn The Moment: Acting, Art and Life

Anthony MeindlIn the Envelope: The Actor’s Podcast

Backstage

Inside of You with Michael Rosenbaum

Cumulus Podcast Network

Inspired by Nick Jones

Nick Jones

Killer Casting

Lisa Zambetti, Dean Laffan

Literally! With Rob Lowe

Stitcher & Team Coco, Rob Lowe

Need To Know

Bryce Zabel

One Broke Actress

Sam Valentine

REAL ONES with Jon Bernthal

Jon Bernthal

SAG-AFTRA

SAG-AFTRA

SAG-AFTRA Foundation Conversations

SAG-AFTRA Foundation

Second Act Actors

Janet McMordie

Six Degrees with Kevin Bacon

iHeartPodcasts and Warner Bros

SmartLess

Jason Bateman, Sean Hayes, Will Arnett

That One Audition with Alyshia Ochse

Alyshia Ochse

The 98%

Alexa Morden

The Acting Podcast from The BGB Studio

Risa Bramon Garcia and Steve Braun