.png)

The Late Bloomer Actor

Welcome to "The Late Bloomer Actor", a monthly podcast series hosted by Australian actor David John Clark.

Join David as he engages in discussions with those that have helped him on his journey as a late bloomer actor, where he shares personal stories, insights, and wisdom gained from his unique path as a late bloomer actor and the lessons he has learned, and continued to learn, from the many sources available in the acting world.

Each episode features conversations with actors and industry insiders that have crossed paths with David who generously offer their own experiences and lessons learned.

Discover practical advice, inspiration, and invaluable insights into the acting industry as David and his guests delve into a wide range of topics. From auditioning tips to navigating the complexities of the industry, honing acting skills, and cultivating mental resilience, every episode is packed with actionable takeaways to empower you on your own acting journey.

Whether you're a seasoned actor, an aspiring performer, or simply curious about the world of acting, "The Late Bloomer Actor" is here to support your growth and development. Tune in to gain clarity, confidence, and motivation as you pursue your dreams in the world of acting. Join us and let's embark on this transformative journey together!

The Late Bloomer Actor

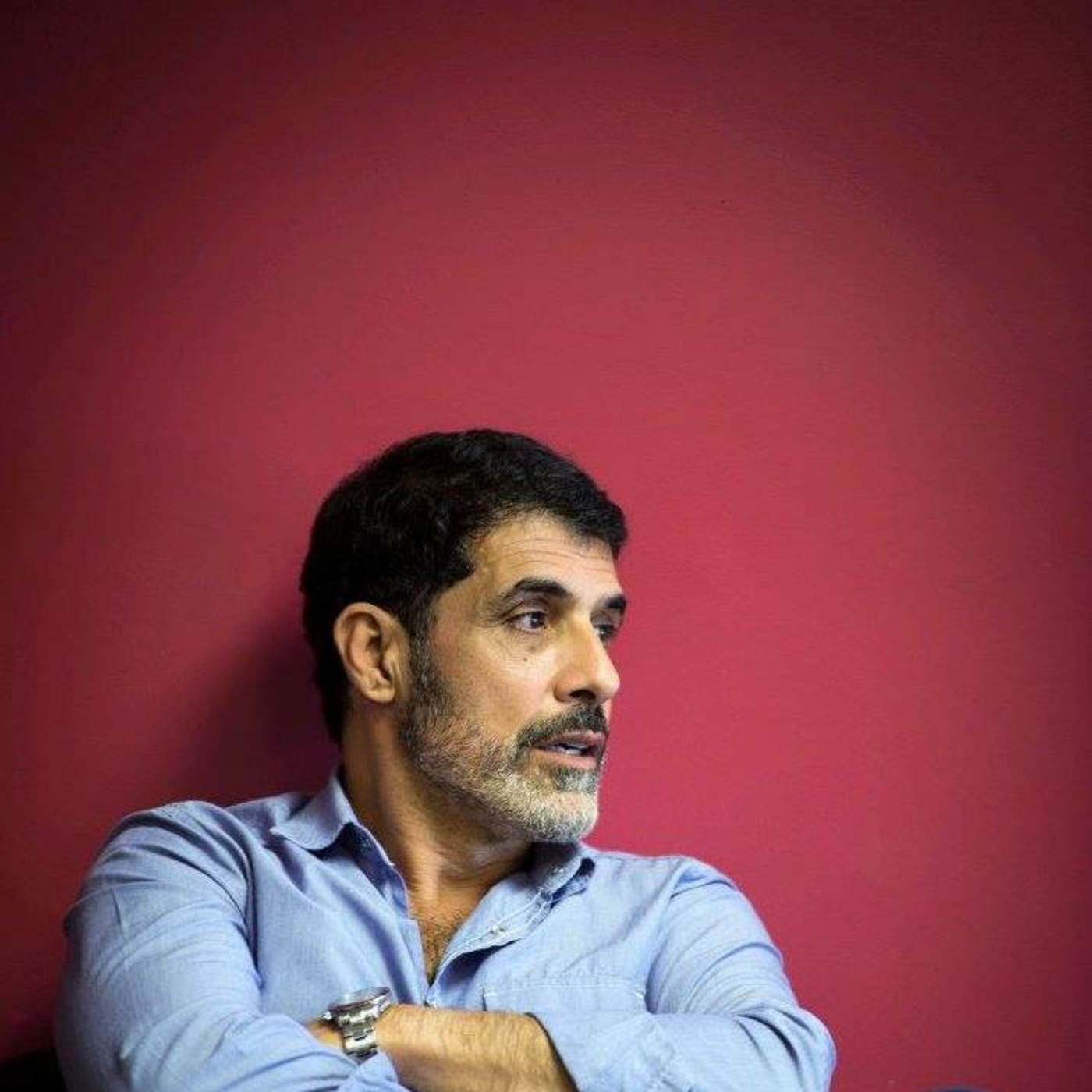

Character Based Improvisation with Robert Marchand

Text The Late Bloomer Actor a Question or Comment.

In this episode, David John Clark interviews Robert Marchand, a director and method teacher, about the intersection of the business and creative sides of acting. They discuss the CBI (Character-Based Improvisation) method, Robert's journey in the film industry, and how improvisation can enhance character development. The conversation also touches on the importance of the actor-director relationship, the role of CBI in auditions, and the mental health aspects of acting. Robert shares insights on how actors can build confidence and resilience in a challenging industry.

Takeaways

- The business side of acting is closely linked to the creative side.

- Robert Marchand's journey to the CBI method was unconventional but enriching.

- The CBI method emphasizes character development through improvisation.

- Improvisation allows actors to explore their characters deeply.

- Actors can use CBI techniques to enhance their auditions and self-tapes.

- The actor-director relationship is vital for a successful production.

- Directors benefit from understanding actors' perspectives and experiences.

- Casting professionals seek authenticity and depth in performances.

- Mental health and resilience are crucial for actors in the industry.

- Building confidence is essential for creative work.

If you're keen on the CBI method, check it out at Character Based Improvisations.

Please consider supporting the show by becoming a paid subscriber (you can cancel at any time) by clicking here and you will have the opportunity to be a part of the live recordings prior to release.

Please follow on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and Tik Tok.

And please Rate the show on IMDB.

This episode was recorded on RiversideFM - click the link to join and record.

And finally, I am a huge advocate for and user of WeAudition - an online community for self-taping and auditions. Sign up with the PROMO code: LATEBLOOMER for 25% of your ongoing membership.

David John Clark (00:00)

Welcome to another episode of the Late Bloomer Actor, where we continue the theme of season four of the business side of acting.

But it does seem through previous episodes that the business side of acting intersects very strongly with the creative side of acting. And today I'm sure that message will strongly reflect the same theme. Today we have a wonderful director and method teacher on board to chat with Robert Marchand. Welcome Robert.

Robert Marchand (00:22)

Thank you, David. Glad to be here.

David John Clark (00:24)

And you can tell it's early in the morning for me. I'm tripping over my words already. I haven't done a proper warmup! My podcast is essentially about my journey as an actor, interviewing people that I have crossed paths with on my journey. And our paths are in that I've been fortunate to assist you in the delivery of your character-based improvisation technique, or easier said, CBI, as an actor inserted into your course for participants.

I'd really like to delve into this method and how it can be an effective component of an actor's toolkit. But firstly, can you give us a brief insight into your career and how you arrived at your current position as an advocate and coach of the CBI method?

Robert Marchand (01:05)

Okay, well, how long have we got is the first thing, but well, I'll give you a sort of kind of edited version. The thing I sometimes mentioned this in workshops when I was 16, all I wanted to do was make movies. And I went as far as to get on my bicycle. I lived in the UK at the time. I had French parents who lived in the UK and went cycled to Pinewood Studios.

David John Clark (01:07)

⁓ As long as you need.

Robert Marchand (01:33)

And discovered that it was like a gated community. There was a sort of doorway with a night watchman sort of person there. And I sort of imagined, had a failure of nerve as a 16 year old. I wasn't exactly the most competent person on the planet. And so I imagined the conversation I was gonna have with this guy. I wanna get a job in the film industry. And he was gonna say to me, piss off, Sonny, or something like that.

And so I thought, okay, this is crazy. don't, you know, and I gave in. My father wasn't very pleased with me. wasn't doing well with exams. I got a job. And so I didn't go near the film industry for more than a decade. And I did lots of work, worked in admin, migrated to Australia, migrated to Australia because I had no relatives here whatsoever. What a relief. And so I ended up

David John Clark (02:27)

I love it.

Robert Marchand (02:32)

whole series of things. By chance, I was handed a 16 millimeter windup camera. I was around 30. And I started to make movies as a total amateur with my friends as actors in my evenings and weekends away from my regular job. And when I was finished, I had this silent 30 minute film that I'd made, was messing around for about a year.

And I wanted to put a soundtrack on it. I had recorded sound, but separately, this is, you know, very primitive filmmaking. So I went to a kind of post-production place in North Sydney, looked one up on the yellow pages and went to this place. And this board technician laced up my film and played it, sat there with his arms folded and then said, you know, there's a place for people like you. It's called the film school.

David John Clark (03:29)

Hahaha

Robert Marchand (03:31)

I couldn't quite decide whether that was a compliment or a sort condemnation of the work. But I didn't know there was film education. I had no idea. So I put this film in and to my amazement, they took me on. And at the time I was around, it was a little after that, but it was about the oldest student they'd ever taken on at the time. So my life changed three years at AFTRS in Sydney. The most amazing experience, the most...

You know, fantastic. It was like a Bunnings for filmmakers. Because you had guys with expertise, equipment on the shelves. You go out and make movies. Nirvana. So I started to do that. And then the end of that, I had a career and I started to, I made lots of short films. And here's the thing that I think relates particularly to the whole idea of the late bloomer. By going to film school,

at the end of my 20s, early 30s. I didn't realize at the time, but I was bringing with me considerable life experience. And I was surrounded by 20 year olds who wanted to make films. And I ended up doing a lot of writing and advising other filmmakers. Anyway, long story short, the end of film school, my short films that I

or produced or directed one three AFIs in one night. And I was standing there on stage looking a bit startled with these three things in my arms. And in the after party, in a classic Hollywood way, this producer tapped me on the shoulder and said, come and see me on Monday. And, cutting to the chase, in effect, I got hired to direct this mini-series, Fields of Fire.

David John Clark (04:59)

Oh, wonderful.

Robert Marchand (05:21)

which was a big deal at the time because it was a big budget. It was about five million dollars or so, which was huge in those days. And a big step up from just being a student doing short films to this. Anyway, so that was my career. That's how I got going. And I did a lot of mini series over the next 10 years or so. I was fulfilling what I wanted to do. Along the way in the journey,

David John Clark (05:27)

Yes, definitely.

Robert Marchand (05:45)

I ended up with an opportunity to direct a mini series in the UK for the BBC. I met the producer and we talked about it. And then the system in England is that because it's so teeming and hard to get around, they give you a car and a driver who drives you everywhere. So I hopped in the car and was driven out to the studio, Pinewood, where I had dropped my bike about

David John Clark (06:06)

Nice!

Robert Marchand (06:14)

16 years earlier and through the doors and into this complex and I sat in this office adjoining an empty studio for us to build for this series and this guy came in he was around my age and he had a sort of rather crumpled suit and a white shirt and a tie and he said hello governor my name's Ian I'm your unit manager do you want a cup of tea? The point is

If I'd gone through the doors as a 16 year old, I'd have ended up being that guy, some gopher on the periphery of filmmaking. So I feel hugely ⁓ blessed that I've been lucky enough on the journey I've been on to arrive where I have.

David John Clark (06:59)

I love that. We

talk about that a lot on the show about the sliding door moments, you know, different doors opening or not opening. And sometimes you end up where you were meant to be.

Robert Marchand (07:10)

Yes, absolutely. I think it's like serendipity of things that happen, the accidents, the chances, you know, of what happened along the way. To bring you up to date, the film industry went through, in Australia, went through one of its sort of periodic downtimes.

David John Clark (07:11)

I love that story.

Robert Marchand (07:29)

And I thought this is an opportunity to actually investigate on a slightly more complete way some of the things that interested me to do with use of improvisation in filmmaking. So I went back to uni, went to Flinders and did a PhD all around everything to do with fictive identity. What does it mean? What do we assume? What can we create? Had a ball doing it and ended up

having a great base for running these workshops I now run, character-based in pro, (CBI) workshops, which are for actors and directors, by the way, equally, yeah.

David John Clark (08:10)

Yeah, and that's, believe your courses have actors and directors all integrated into that training and then they work together. Is that correct?

Robert Marchand (08:18)

That's right. Yeah, it's two strands common purpose. Yeah.

David John Clark (08:23)

Okay.

Now I read somewhere that Director Mike Leigh is an influence of the CBI method. How does that work? And can you give us a bit of an insight into the CBI process itself so that if anyone's looking for an improvisation type training, they know what they're going to get?

Robert Marchand (08:42)

Okay, so the Mike Leigh connection is that he's probably the best known practitioner of a CBI method, even if he doesn't use that terminology. He creates whole films. He uses improvisation to create characters and relationships to evolve dramatic possibilities. Then he distills the whole thing and fashions a film and then he goes and films it.

There are variations over the years as to how he works, but that's the essence of what he's doing. CBI is slightly different in the sense that not everybody is Mike Leigh. 99.9 % of the world are going to have to have a script and a document to persuade investors, producers, stakeholders, who name it. So that immediately says,

David John Clark (09:27)

Hmm.

Robert Marchand (09:37)

the improvisation process needs to be adapted into an understanding that we're going to go and make this film. As an aside, Mike Leigh has this thing where with his producer in the past, when he was ready to make another film, his producer would go into the city of London and say things like, ⁓ Mike's ready to make another film, go and see film friendly banks. And they'd say, okay, what's it about? Can't tell you that. Well, can we see a script? No, there'll never be a script.

David John Clark (10:05)

There isn't one.

Robert Marchand (10:07)

But what's it about? Can't tell you. How much does he want? Well, he's looking for four million. Four million, we'll give him one. So you do that four times, you got your budget. Not many people can do that. So for the rest of us who are going to go to Screen Australia or various local bodies, you're going to end up with some kind of document to identify your film. Sometimes it's a complete script. What CBI does is to say, okay,

David John Clark (10:14)

Ha

Fair enough.

Robert Marchand (10:36)

We know there's a script, we know where this is going to go. People who sign on to do this, whether they are actors or whether they're crew, have an understanding of the genre, the type of film you're making. How did these characters get to be the way they are? And if we begin a journey by investigating these characters with the actor, building the characters, building a history and a backstory,

something of the experiences they've had at high school, in early jobs, wherever, whatever age they are. We end up with insights for the filmmaker to go, that's interesting. That helps fuel one of my strands in the film that I want to develop, or indeed is a better idea than I had for this particular scene. And actors are bringing a tremendous depth and complexity to their characters because they know the character inside out.

So you can go back to the script now, re-informed by the development journey. And you can also use CBI in between scenes when you're shooting to help the actors be right on the button for the next scene you're filming.

David John Clark (11:50)

That's interesting. So how does that cross over? So, with the training that I've done with you, I've been on the other side. I've been given a task to come in as a day player, so to speak. My first one, ⁓ are you allowed to give away some of your secrets or what I did? Is that giving away secrets? Are you happy to talk about that? I'll rephrase it. rephrase it. So I've been given direction to come in and

Robert Marchand (12:10)

It is giving away secrets. It's okay.

Ha ha ha ha.

David John Clark (12:18)

produce something or say something and then the other actors are working with their stories and everything and then they react to whatever I'm giving them and that could be as simple as me just knocking on a door. How do you convert that from your training? So in the training, there is completely no scripts, you've given them the storylines and their characters and they build it. So how does that then correlate when they get a script? Is it the same process? Because obviously then they've got to remember their lines and do that. You're saying it's building a, does it,

your training builds something so that just becomes a natural flow once they've got a script in hand.

Robert Marchand (12:55)

The idea is, hopefully, that the work one does in improvisation through a CBI process is that you are exploring states of being, mental states, attitude, worldview in a character that in some way is going to have a significance in the film. So if you had, as a simplistic thing, a prejudiced police officer,

for example, who's got an attitude towards things. How did that person arrive at that? Why did they have that view? Is it something they received through social media? Or is it through direct contact? Is it through experiences? We might investigate that. So that rather than having a kind of simplified cop with attitude, you've actually got somebody who's got much more sides to them, more for the actor to play.

More for an audience to respond to. It's helping you get away from the obvious very often and making the investment in the film and the characters, the relationships, just altogether more satisfying, it seems to me, is one of the things that's happening. The actors can fly with the scenes because now the words on the page are not words to learn. They're naturally what they're going to say,

in these circumstances.

David John Clark (14:17)

It's interesting. if I'm an actor and I've been playing a police officer and my line is, ⁓ sir, do you know what you speed you were doing back there? Now, if that's all I'm doing, whether it's in an onset or an audition, I might just say that, sir, do know what speed you were doing back there? But I can see the benefit that if I've sat down and talked about him having these prejudices and ⁓ his history and I talk about, you know, for whatever reason, he's all these different things that have led him to become an

an asshole for a better word, then that might change that single line dramatically. Is that what we're aiming for?

Robert Marchand (14:55)

In fact, and just building on what you're saying, that for instance, as a filmmaker, I would think originally I just had in mind to film the copper as he appeared in the window from a kind of driver point of view, but hearing, you know, having worked on this and discussing it, actually, the moment that is most telling about this copper is getting out of his car and approaching this car, we can get something of an attitude and a feeling of, is he tentative? Is he sort of

unbuttoning his sidearm or something. In other words, there are things to play beyond just the lines. And presumably having spoken his line, there's a response and probably in editing a cut back to the police officer who might then be having to wrestle with his prejudices that the person who answered him is well-spoken, polite, nice, et cetera. Therefore...

Okay, revision of thinking. All of these things are there, things to be able to investigate.

David John Clark (16:00)

It's interesting, isn't it? Because a lot of people say, when you talk the word improvisation, that they say, well, you're not allowed to do that in a lot of sets because you, the script is a script and especially certain writers, you're just not allowed to change the script. But that doesn't matter because the end of the day, how the actor walks and how the actor stands, unless he gets real particular direction from the director is up to the actor. So if you've got this in the back of your head and all these processes, I can see the benefits of how much

just a walk for 30 seconds or 10 seconds could change that character on screen for the benefit of everybody. It's wonderful.

Robert Marchand (16:37)

There's a secondary thing that's not necessarily very often foregrounded, which is the actor who's had a bit of process has had time to get familiar with the character. And therefore, when they are on set and working, very often the uncertainty or even nervousness that the actor might feel is gone because they have certainty about who the character is, what the character's doing.

You know, now it becomes a technical exercise. Here's your mark. There's the car. There's this, but they are no longer trying to process everything on the run, on the run. They are fully grounded. And I think that's tremendously valuable.

David John Clark (17:20)

It's interesting and bringing it back to the business side of acting and how we cross over with that, ⁓ the creative side and the business side. In a market where actors are constantly pitching themselves, how do you think the CBI process could help an actor stand out in their auditions or self-tape so before they're on set?

Robert Marchand (17:40)

I do quite a lot with the CBI and auditions and it's an element of workshops that I'm always inviting actors to give me feedback about their experiences and to see how we can help. Routinely when I'm auditioning myself, rather than sending people pages of a script, I will send them a kind of biographical background on the character and say,

please absorb this. Please think of a circumstance unrelated to the script, which by the way, they will also have seen so that they're not going completely blind, but come up with a situation that you can explore in an improvisation in a self tape, have a scene partner who's just off camera. So the eye lines and all the technical sides of it are good. The audio is good. And

record something. In particular, what I'm looking for is the opportunity for the actor to exercise their inventiveness with the character. So that they're able to not just take, I've learned who the character is and I understand the situation. What would this character be like away from the situation in the movie? Are they much more relaxed and expansive? Are we getting a contrast? I'm happy to see that.

Even though on one level you say, well, that's not related to the film. What I'm seeing though is actor inventiveness within a character rather than just being inventive for the sake of inventive and giving them the opportunity to, in a way, if you like, showcase their skills.

David John Clark (19:26)

So in the case of an audition, you're very rarely given a full character breakdown. You're you're police officer number one, here's your line, sir, do you know what speed you were doing back there? Would you encourage them that actors use the CBI method and develop their own backstory or something like that based on what they have a feel for what the script is asking?

Robert Marchand (19:47)

I think I would. Yeah. mean, it's, let me be a little more specific. I absolutely would. The thing is that you can say, okay, the scenario is, let's say a police officer in a country area of Australia. All right. How come he is there? Is he a transplanted cop from a city? If something happened, it may not be anything to do with the film, but it helps to kind of,

establish things that are helpful to the actor in coming to this character. So from an audition perspective, we're inviting the actor to make decisions about what they're going to do. When we have conventional auditions, it sometimes happens that an actor will come to an audition session where we're dealing with a casting agent, we're in a studio and say things like, how would you like me to play this? And I say,

the trouble is that only works if you've got an empathic, articulate director. But you might have, sadly, some technician who's as terrified as the actor. Says, I'm not going to do that. And now you've got to make a decision and it's unhelpful. Whereas if you said, OK, I'm going to play this guy like this, now it's definite and it's strong and it's confident and it's with all the research behind it. If the director says, whoa, whoa,

don't want that. I want this. You can put your preparation in your pocket and you're ready to go with an alternative. It's a much stronger way to approach it. So I apply the same thing to self taping, make a decision, be determined about it. That's your take on it. From a director point of view, I can review the tape and say, okay, that's interesting what you've done. Now I'd like to play with it a bit. What if we said he wasn't quite like this, this had happened and that had happened.

Let's do something more. So we're, you know, in a way working with creative raw material.

David John Clark (21:49)

So on the fly, you can change it. So if you've gone in there, you've done a whole backstory and made the police officer an arrogant racist, for example, and then they come in and go, hang on, no, we like what you've done there, but this guy's just having a tough day and play it like his wife's pregnant. He didn't want to go to work today, he's been called in. So on the fly, you could quickly develop, use the CBI method in the background, come up a minute or two in your head and then bang, throw it out.

Robert Marchand (22:18)

The

sort of thing I'd sort of say, and it does depend a bit on the actor because one doesn't want to undermine their confidence, would be to say, that version you've just given me is how he was five years ago. Five years ago, he met an indigenous woman and fell in love with her. And lots of his prejudice went out the window and he saw things from another perspective. Give me an updated version of this guy now where those things no longer apply.

David John Clark (22:24)

Hmm.

Robert Marchand (22:47)

So although it's a sketch, it's something to hang onto that allows the actor to go, okay, all right. And it's evolution. So it's rather than saying, you're wrong, get rid of that. It's sort of making use of what was there.

David John Clark (22:58)

Hmm.

I like that. And obviously you can feel that just with that experience of that background of playing characters in that way, that the more you do it, the easier and the quicker that switch from one type of character to another would occur. Have you seen that in actors that you've trained?

Robert Marchand (23:17)

Yes, to answer your question, there is a little bit of a backup to that, which is it's my view that actors are transformative people from the get-go. And they do amazing things. I'm not an actor, never trained as an actor. So I'm always impressed with an ability for somebody to pretend to be someone else so completely that they feel significantly different.

We take it for granted when we see the Hollywood stars do it, but it's possible at all sorts of levels of experience. And therefore, what I'm saying is the actor should get used to the idea that they're never just simply playing themselves. Of course, it's their physiology and there are certain gestures and habits that may come through, but to be able to inhabit the mindset of someone else,

is why I use CBI because it's going to give you loads of background material to tap into to be able to construct somebody who is not you and then have confidence in continuing to play that character.

David John Clark (24:22)

And obviously you can feel that just with that experience of that background of playing characters in that way, that the more you do it, the easier and the quicker that switch from one type of character to another would occur. Have you seen that in actors that you've trained?

Robert Marchand (24:37)

Yes, to answer your question, there is a little bit of a backup to that, which is it's my view that actors are transformative people from the get-go. And they do amazing things. I'm not an actor, never trained as an actor. So I'm always impressed with an ability for somebody to pretend to be someone else so completely that they feel significantly different.

We take it for granted when we see the Hollywood stars do it, but it's possible at all sorts of levels of experience. And therefore, what I'm saying is the actor should get used to the idea that they're never just simply playing themselves. Of course, it's their physiology and there are certain gestures and habits that may come through, but to be able to inhabit the mindset of someone else,

is why I use CBI because it's going to give you loads of background material to tap into to be able to construct somebody who is not you and then have confidence in continuing to play that character.

I'm not sure if I answered your question there actually.

David John Clark (25:45)

No, no, definitely

did. Yeah. It's about how it rolls on. So once you've left the training background and you use that method, how does it build your toolkit, so to speak, is more what I was focusing on that certainly answered it. So you were talking before that you've never been an actor. So you're from your director and your teaching side of things. What ways does CBI strengthen that actor, director relationship and how important is that relationship to

you sustaining a long-term career in this business.

Robert Marchand (26:16)

The first thing I would say is what would seem like a no brainer probably is I have considerable respect for actors as a start and actors always have lots to contribute. They've got ideas, they will see a script. Sometimes at rehearsals and round table script readings actors will offer things and say, you know, I wondered about this and I saw this in the script and what about that?

It seems to me that there's a value in listening. That's a starting point. And it's a clue as to the amount of the potency, if you like, of what an actor can contribute. It's not uncommon for filmmakers nowadays, now that I do a lot of mentoring along the way, by the way, but it's not uncommon for filmmakers to come along and

invite me to be involved using CBI process at a writing stage. We might bring in some actors and actually bring these characters to life. The writer goes, oh, wow, okay, now I see this happening. I can see things I can change things I can make better, and so on. That's one side of it. I have a sense I'm drifting a little bit you should

David John Clark (27:35)

No, I

love drift. This is what's good about interviews because I can give you as many questions, but we get the nuts and bolts when you drift. So keep drifting. I love it.

Robert Marchand (27:44)

Well,

somewhere in there was a question you asked me and I have a feeling that I went off on a writing gig there for a minute.

David John Clark (27:49)

It

was the actor-director relationship and how that can build their career in the business, so to speak. So obviously the director will know what he's going to get from that actor and he will call on them again.

Robert Marchand (28:03)

Yes, in fact, your question was about because I was not trained as an actor myself, I think. it begins from an appreciation. What's happening when you think about it is that there are a great many creative people involved in the business of making a movie, but there's a primary relationship between the director on set, obviously, and in rehearsals and the actor. We've got two creative artists who have slightly different

David John Clark (28:08)

Hmm.

Robert Marchand (28:31)

agendas and objectives, but the one thing they have in common always is the character. The director wants this character to exist within a narrative and have various functions and have various outcomes to have an impact on the audience. And the actor wants to understand the character and make this character come to life as completely as possible. So it seems to me that one of the things that I'm always encouraging directors

is to engage in dialogue with actors. There's a whole sort of spiel, if you like, I do in workshops about the nature of this relationship. From an actor perspective, I think what I'd be looking at is to say a script is a template for the character you're going to play. You have context of what's happening to this character through the script.

You might have an objective view about your character as an actor because you can see that the character maybe is like a catalyst in the drama, has a function to play in narrative terms. All that is totally fine. But that context means now you can say, okay, who is this person? And what else would be nice to know about them? Sometimes you can ask a director or the writer,

if they're the one and the same person. And, with luck, you get a good response. And sometimes you do it yourself because for whatever reason, there's either no time or no opportunity. But making some kind of decisions about that seems to me to enrich what the actor can do with their character.

David John Clark (30:17)

That's wonderful. That's wonderful. And sort of bringing it back to your workshops and the CBI process itself, we haven't talked about the director side of it. So what's the difference between what you're teaching directors as opposed to actors? Because obviously the director's not going to improvise so much. How is that different? Because I would have listeners on here who might just be directors, but there would also be plenty of actors who might cross over and do both sides.

Robert Marchand (30:44)

For sure, yeah, okay. So I think there are several messages for director perspective on CBI. It's not uncommon for there to be terrific technical training for directors. They are given an immense array of possibilities and it's a common theme. I teach at film schools

across Europe as well as in Australia and different places. And it's extraordinary how similar they are. It's extraordinary how similar the architecture is. It's like the same bloke went around the world creating film schools, but I leave that to one side. And so they end up with tremendous technical training, but the amount of contact they have with actors is generally limited. And sometimes the contact is through an affiliated drama school.

David John Clark (31:24)

You

Robert Marchand (31:41)

And of course, when you put trainee directors with trainee actors together, the results can be uncertain. Am I not getting the results I want because I'm not fully developed as a director yet, or is it that as an actor, they're still themselves in training as well? And indeed, I do quite a lot of work where I bring the two schools together and run workshops where we are establishing a kind of benchmark.

But the main thing for me is that from a director point of view, the more contact you have with actors in general and specifically project by project, the better this is. It removes any sense of the phobia that has sometimes been described around director to actor relationships from the director perspective. Actors, in my view, are generous,

open, very committed, want to be there, want to contribute as much as possible. And it's in the director's hands to develop a relationship around those positives. So, one thing is it immediately makes the contact very human. You know, I routinely will go and have a coffee in a social environment with an actor who I'm going to work with,

so that we're not sitting in a rehearsal room, everyone else is waiting and watching as we talk about stuff. It's not that I want to make the actor my friend, but I want to be able to have a sense of where they're coming from. I will often say, what's your take on this character? And it may lead to, what's your take on life? And to understand that can be also quite helpful. You know, for an actor to be able to say, this guy is a million miles from me.

David John Clark (33:12)

Hmm.

Mmm.

Robert Marchand (33:32)

Like, you know, he's so naive and this and this and this, and, you know, is giving us information that is not necessarily, I'm going to use this in directing, nothing like that, but of an understanding of another human being. Seems to me, developing an element of empathy and understanding as a director makes you a better writer director apart from anything else, but also means it gives you more

means of communication with the actor. In an ideal world, when you're on set, your communication with the actor is immensely brief. Between takes, you want to be able to just have a quick word, yeah, okay, we'll do it and change something. And all of that is the tip of a very big iceberg, if you like, or pyramid, maybe it's a better analogy, that is representing all the previous work, you know.

David John Clark (34:29)

Yeah, I can see that benefit in that relationship, especially when you've got a bigger role or something's more meaty or, you know, dealing with issues that, you know, a lot of us don't deal with in life that we know that a lot of people do because that can be heavy for an actor and crew just watching it. Having the trust of the director to know that how you're feeling and having been able to recognise that he needs to step in, say, all right, let's have a break or let's approach it this way is fantastic. I like that emphasis on that relationship.

Robert Marchand (35:00)

I think that it's by the time you get to filming, you have a very strong idea about the way in which this particular actor is going to not only approach the character, but probably play a great many scenes. You don't absolutely know because of course there is the magic of when the camera turns. There's another 10, 15 % of performance that naturally comes out based on

previous preparation. But all the same, you are in the world of now knowing what is going to work best from the actor's point of view in terms of prep. So scenes of intimacy, for example, I have a whole set of processes I use in order to help actors who are going to play sex scenes or other forms of intimacy, whatever it is

and to be able to manage also the crew aspects to it as well so that there is a holistic approach to doing this kind of work.

David John Clark (36:08)

That's wonderful. The CBI method emphasises that there's this authenticity, so to speak, and behaviour. We've been talking about that today. In your view, is this something casting professionals are craving more of today?

Robert Marchand (36:22)

So there is, I think there's a value in recognizing the subtly different types of acting required for different circumstances. So if we talk movies, the script is going to give you some sense of, for instance, stylization on a film. If you read the script for Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, you would have a very quick sense of the nature of the kind of film you're making.

And someone auditioning for a part in that is going to hopefully adapt and adjust their performance. If you're doing television work, it may be genre related, but mostly it is steeped in a kind of naturalism of ordinary folk and then extraordinary things happen, let's say. So that's an adjustment of performance. If you are going for a commercial,

now we're in a more stylized world where the nature of the commercial means there's a tendency for those doing the casting to want to already see what they're going to put on screen. So there's a kind of precision and type. They want tourist number two to be just like that. you know, the recognition of these different stages mean that you are able to adjust. That's pretty useful to be able to do that, I think.

David John Clark (37:47)

I like that because we're in a very changing environment for what type of productions are out there. There's a lot more recruiting people off the street, that real life person, someone with no acting background. I just wanted to ask you, bringing it mainstream today, I don't know if you've seen it yet, but you surely probably heard about it, the TV series Adolescence being filmed in that one take process.

Robert Marchand (38:13)

Yeah.

David John Clark (38:14)

If you were to take on that project, how would you implement the CBI method in that? Or do you think that they've done something with that? Because I'm sure that if you're doing one take and I know, I believe they've had a script, surely they, I mean, it's essentially a play with a camera, isn't it? But do you see where I'm leading there?

Robert Marchand (38:32)

It's

I do I do I do I've watched it and yes, I think it's a terrific series. I think that there are several things about it let me first of all deal with the one take aspect because on one level it could be dismissed as a gimmick and I don't think it is I think it's a very integral part of the work. One of the things that happens is

David John Clark (38:51)

Hmm.

Robert Marchand (38:57)

whether you knew beforehand that it was only one shot or whether you didn't and you were just engrossed in the drama. In episode one in particular, the manner in which the whole thing is delivered to the audience from the breaking in of the door, what seems to be an excessive use of violence by the police to arrest this teen boy and then the processes of going to the police station and so on.

There's a tension induced, a very subtle mise en scene by having the camera never blink, by keeping it one shot, by following somebody and then you go somewhere else. I think it's a tour de force. The first episode especially is very effective, establishes all the players, sees them in their professional roles as police officers or whoever they are, lawyers and so on. It presents us with

the sense of for the boy, this relentless ongoing nightmare that he's suddenly enmeshed in. I thought it was very, very effectively done. The use of the single shot was very powerful. The same drama done with editing. It's amazing you realize how much we are let off the hook by cuts and so on. It makes for smooth filmmaking. We're all very practiced at it.

David John Clark (40:21)

Mm.

Robert Marchand (40:22)

The disciplines involved in that are very strong. So that was one thing that really jumped out at me about that. In terms of preparation, I have no doubt that whether it was acknowledged as a CBI type process or not, that there was a tremendous amount of detail provided. There's undoubtedly a script and certainly when we're dealing with, for instance, police,

interviews with the boy and later in the later episode the psychologist interview with the boy that wasn't it you know

David John Clark (40:56)

Oh, that was just amazing to watch. It was just so

long and it was just, it just kept going and going and it just, you were on the edge of your seat the whole time. It was amazing.

Robert Marchand (41:05)

Absolutely,

Absolutely. It's interesting. It reminds me of a quote by Mike Leigh from one of his very early films when he was being asked about it by a journalist about sometimes you arrive at situations that are really intolerable. You want to look away. You want it to stop, but it goes on inexorably. And that came to mind when I was watching that journalist's interview or discussion. Yeah, yeah, totally.

David John Clark (41:28)

I can see that.

It was interesting, they were talking about, Greg Apps was mentioning the same show and Gogglebox, I don't know if you've watched Gogglebox here, which is TV where we see people watching shows. So all these people, these different families all watch a variety of shows on Foxtel and TV, and then we see how they react. And most of the time they're sitting back in their couch and watching and commenting and et cetera, et cetera. But for this particular show, it was...

they were all sitting forward. They were all sitting on the edge of the seat for, for wanting, for that saying. And that really showed the difference. And I was talking to my wife about, it that one take approach ⁓ or is it the this just boils down to the story again? You know, what was happening? It was that good. It was hard to call. So.

Robert Marchand (42:19)

I think the subject matter is very compelling and is striking a chord with a great many people. It's certainly striking a chord with parents, obviously, who are, as each generation comes along, wrestling with the differences with what their children are interested in and so on, and confronting the whole unease we have with the degree of social media and the young age that people are absorbing that.

David John Clark (42:31)

Mm-hmm.

Robert Marchand (42:49)

So in that sense, I think there's a tremendous compellingness about the subject matter. We shouldn't ignore the fact that the performances are fantastic, that all of the actors all the way through, from the dad, the boy, the psychologist, I think there's some really super work. And I'm guessing that without knowing anything of the background,

David John Clark (43:00)

Oh, yeah.

Robert Marchand (43:13)

that something like this process, a CBI type process, was undoubtedly used in order to examine all kinds of background stuff. To be able to have those interviews, there are going to be times when the boy is asked things that may have a scripted answer, but the depth of knowledge behind it is a key factor. So he has friends, one of whom is later interviewed.

Well, to be able to discuss the friends is more than just on paper, I've got a friend, that actor's playing him. It's actually the, almost certainly some kind of work has been done between the actors to establish the basis of the friendship. Yeah.

David John Clark (43:58)

I love it. I love it. And I can really

see the depth of where the CBI process can give you those tools as an actor. I just wanted, as we wind up, bring it to something that is as big for actors around the world now. So many actors struggle with rejection and resilience. So does the CBI method provide psychological or emotional tools that could support an actor's mental health in the business?

Robert Marchand (44:23)

Yes, it does in a short answer. One of the things that I'm always emphasizing is to recognize the actor as an artist is about to pretend to be someone else, but they're not just an extension of themselves. I'm always investigating whether as we develop the character, are we accidentally inadvertently straying into areas that have discomfort for them,

into something that, you know, they've had trauma in their own lives and this is mirroring it in some way. In other words, that we have a dialogue about that and we make adjustments if we can. In workshops, that's very easy. With scripted work, there's an understanding when an actor takes on the job that in the script, for instance, a parent dies, this might have happened to them.

Does this have an impact? In other words, we are recognizing the whole person. That's one thing. The other aspect is when the actor is in character, they are fully inhabiting the psychology of the character. When it's over, one might say, okay, come out of character or cut or whatever, but it's still resonating for the actor. And to have

a kind of cool down time and mechanisms for dealing with that becomes quite important. So yes, it is a big thing for me about that. David, there was one thing I wanted to try and slip in that may need to go in earlier, and it was to do with the process of CBI that I somehow haven't managed to include something I just thought might be useful to talk about. And it was sparked by

David John Clark (45:48)

Mm.

Mm-hmm.

Robert Marchand (46:10)

referencing adolescents. One of the things that CBI does is to place the actor in a position that they know no more than the character knows, so that they're in a state of what I would call creative obliviousness. So when we're doing this work, the actor

knows there's a script somewhere, but we've quarantined the script and we're investigating maybe times in the past or times a few years before the script. Whatever's happening in that environment, one could, the actor or the character could speculate, this will happen, but they don't know for sure. We're working on the basis of we know who we are, like you and I talking now, but we don't know what's going to happen next.

David John Clark (46:42)

⁓

Robert Marchand (47:04)

And therefore, when we're in character, we're going to respond to stimulus and provocations on the unexpected as the character. That only happens after you've done a bit of this work so that you're thoroughly grounded in it. But it's very powerful because it allows the actor to make discoveries. Wow, I never realized this guy was so jealous when he mentioned this and that. My guy, arced up!

David John Clark (47:14)

Mm.

Robert Marchand (47:31)

It comes back to this business of the separation of actor and character that I'm always asking the actor to talk about the character in the third person as if they just left. So we can do it anyway.

David John Clark (47:40)

Okay.

No, no, I like that. Certainly. I could see the benefits, especially when a filming process is done segmented, unlike the TV show we just talked about, which is done all in one hit. But sometimes you might be feeling the filming the end scene ⁓ and then a week later you're doing the opening scene. So having you in the moment and your brain from a character perspective, but as an actor perspective, not knowing

what's happened in the past, not what's happened in the future because you know the script, but going with the moment, so to speak. love that. Thank you.

Robert Marchand (48:17)

Yeah. Yeah.

David John Clark (48:19)

Robert, that's been fantastic. Thank you very much. Before we do finish up and say our goodbyes, I've been asked to resurrect a question from season one that strangely I never continued with. A lot of podcasts have something that they do at the end of the shows. A common one is the fast paced questions, but I didn't want to be the same. So I came up with something, but I don't know why I dropped it. I just missed it and forgot about it, but I'd love to bring it back. So putting you on the spot.

What would be your t-shirt quote? Meaning if you went to a party or a similar situation, had to put a personal quote or a thought onto a t-shirt, what would it be? Now it could be anything, whether it's from your training for CBI or your life as a director or just what you believe in. It's just a question I love to throw out there.

Robert Marchand (49:06)

I think whimsically I would say something like, it's a t-shirt remember, so there's not a lot of space for words here. If things look bad, come out of character.

David John Clark (49:13)

Yeah, exactly.

Robert Marchand (49:21)

May not be the most deep thing to come up with.

David John Clark (49:21)

Nice. Nice.

Well, it's also it's good because sometimes I've had people say a quote that's just there, you know it, you understand it straight away. That one elicits a response, elicits a discussion. So you walk into a room with that shirt on, it's going to get people talking. I love it. So ⁓ thank you very much, Robert. It's been an absolute pleasure to have you on the podcast. I will ask you one last question before we go. If an actor asked you for one piece of advice that they could implement to enhance their career.

What would it be?

Buy your t-shirt.

Robert Marchand (50:04)

Find ways to build your confidence. Do whatever it takes.

Confidence is a tremendously undervalued aspect to creative work. We all live in a world of super uncertainty and self doubt. And if we didn't mess up, we wouldn't learn things. But, finding a mechanism that makes you go, I'm going to build from that, your confidence seems to me significant.

David John Clark (50:16)

Definitely.

Awesome, awesome. Thank you very much. That's been wonderful. Where can people find you and find out about the CBI method and see what courses are coming up? I believe you run them around the world.

Robert Marchand (50:45)

I do, yeah, a lot in Europe, a lot coming up in Europe in the next year and a half or so. Character based improvisation.

cbieworkshops.com is the website.

David John Clark (50:56)

I'll put the link in the show notes and anything else that can link people to find out where you are. So this has been wonderful.

Robert Marchand (51:02)

Thank you very much

for having me on the show too, much appreciated.

David John Clark (51:06)

Thank you. It's great to have a chat with you. As I said, we have worked together, not in the context of me being one of your trainees, but me working with you and working with your actors, which I love doing because I know a lot of the actors here in Adelaide when you run your courses here. And once this episode comes out, we would have already done another session here in Adelaide. So there's, I'm sure, some great actors looking forward to working with you. So thank you very much, Robert. It's been a pleasure. And as I like to say, we'll see you on set.

Robert Marchand (51:37)

Thank you. Thank you very much. It's been good.

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.

The Real Life Actor

Jeff Seymour

Audrey Helps Actors Podcast

Audrey Moore

Tipsy Casting

Jessica Sherman and Jenn Presser

Castability: The Podcast

The Castability App

Wendy Alane Wright's Secrets of a Hollywood Talent Manager Podcast

Wendy Alane Wright

Think Bigger Actors Podcast

DaJuan Johnson

ACTORS! YOU ARE ENOUGH!!

Amy Lyndon

Act Bold - Where Talent Meets A Plan

Act Bold with Anne Alexander-Sieder

An Actor Survives

Emily McKnight

Podnews Weekly Review

James Cridland and Sam Sethi

Buzzcast

Buzzsprout

Box Angeles (for Actors)

Mike 'Box' Elder

Brian Breaks Character

Brian Patacca

Celebrity Catch Up: Life After That Thing I Did

Genevieve HassanCinema Australia

Cinema Australia

Don't Be So Dramatic

Rachel BakerEquity Foundation Podcast

Equity Foundation PodcastIn The Moment: Acting, Art and Life

Anthony MeindlIn the Envelope: The Actor’s Podcast

Backstage

Inside of You with Michael Rosenbaum

Cumulus Podcast Network

Inspired by Nick Jones

Nick Jones

Killer Casting

Lisa Zambetti, Dean Laffan

Literally! With Rob Lowe

Stitcher & Team Coco, Rob Lowe

Need To Know

Bryce Zabel

One Broke Actress

Sam Valentine

REAL ONES with Jon Bernthal

Jon Bernthal

SAG-AFTRA

SAG-AFTRA

SAG-AFTRA Foundation Conversations

SAG-AFTRA Foundation

Second Act Actors

Janet McMordie

Six Degrees with Kevin Bacon

iHeartPodcasts and Warner Bros

SmartLess

Jason Bateman, Sean Hayes, Will Arnett

That One Audition with Alyshia Ochse

Alyshia Ochse

The 98%

Alexa Morden

The Acting Podcast from The BGB Studio

Risa Bramon Garcia and Steve Braun