.png)

The Late Bloomer Actor

Welcome to "The Late Bloomer Actor", a monthly podcast series hosted by Australian actor David John Clark.

Join David as he engages in discussions with those that have helped him on his journey as a late bloomer actor, where he shares personal stories, insights, and wisdom gained from his unique path as a late bloomer actor and the lessons he has learned, and continued to learn, from the many sources available in the acting world.

Each episode features conversations with actors and industry insiders that have crossed paths with David who generously offer their own experiences and lessons learned.

Discover practical advice, inspiration, and invaluable insights into the acting industry as David and his guests delve into a wide range of topics. From auditioning tips to navigating the complexities of the industry, honing acting skills, and cultivating mental resilience, every episode is packed with actionable takeaways to empower you on your own acting journey.

Whether you're a seasoned actor, an aspiring performer, or simply curious about the world of acting, "The Late Bloomer Actor" is here to support your growth and development. Tune in to gain clarity, confidence, and motivation as you pursue your dreams in the world of acting. Join us and let's embark on this transformative journey together!

The Late Bloomer Actor

UBI and the Arts: Benefits Beyond a Universal Basic Income with Conrad Shaw

Text The Late Bloomer Actor a Question or Comment.

In this episode of the Late Bloomer Actor podcast, host David John Clark dives into the concept of Universal Basic Income (UBI) with guest Conrad Shaw, an actor and advocate for UBI. They explore how UBI can provide financial stability for creatives, allowing them to focus on their craft without the constant pressure of financial insecurity. Conrad shares insights from his work on the Bootstraps project and discusses the potential societal benefits of UBI, including increased creativity and reduced poverty.

Takeaways

- UBI provides a financial floor for everyone, allowing people to pursue their passions without financial stress.

- Conrad Shaw's Bootstraps project explores the real-world impact of UBI on individuals and communities.

- UBI can lead to increased creativity and productivity by removing the fear of financial insecurity.

- The concept of UBI is gaining traction globally, with various pilot programs showing positive results.

- UBI is not about replacing work but enhancing the quality of work and life.

- Financial stability through UBI can lead to healthier risk-taking and innovation.

- UBI can reduce poverty and inequality by providing a basic income to all citizens.

- The arts and creative industries stand to benefit significantly from the implementation of UBI.

- UBI encourages a shift from survival mode to a focus on personal growth and contribution.

Find Conrad on LinkedIn.

For information on Comingle.

For information on The Bootstraps Project.

And certainly check out the ITSA Foundation.

Please consider supporting the show by becoming a paid subscriber (you can cancel at any time) by clicking here and you will have the opportunity to be a part of the live recordings prior to release.

Please follow on Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and Tik Tok.

And please Rate the show on IMDB.

This episode was recorded on RiversideFM - click the link to join and record.

And finally, I am a huge advocate for and user of WeAudition - an online community for self-taping and auditions. Sign up with the PROMO code: LATEBLOOMER for 25% of your ongoing membership.

David John Clark (00:00)

Welcome, welcome back to the Late Bloomer Actor 2026 and our first episode of season five. Can you believe it? Season five. Thank you very much for joining me on this journey for five years now going into our fifth year. So absolute pleasure to do this journey with you. So I'm your host, David John Clark. You obviously all knew that. Today, a little bit different to start the year off with, but we're diving into a topic that I've been fascinated by

for years, something that sits right at the intersection of creativity, community, financial wellbeing and the future of work. It's called Universal Basic Income or UBI. Now, if you've never heard of UBI or maybe only came across it during COVID when governments around the world were suddenly giving people direct financial support, you're not alone. But in the time when the divide between the haves and the have nots is widening, when jobs are becoming less stable,

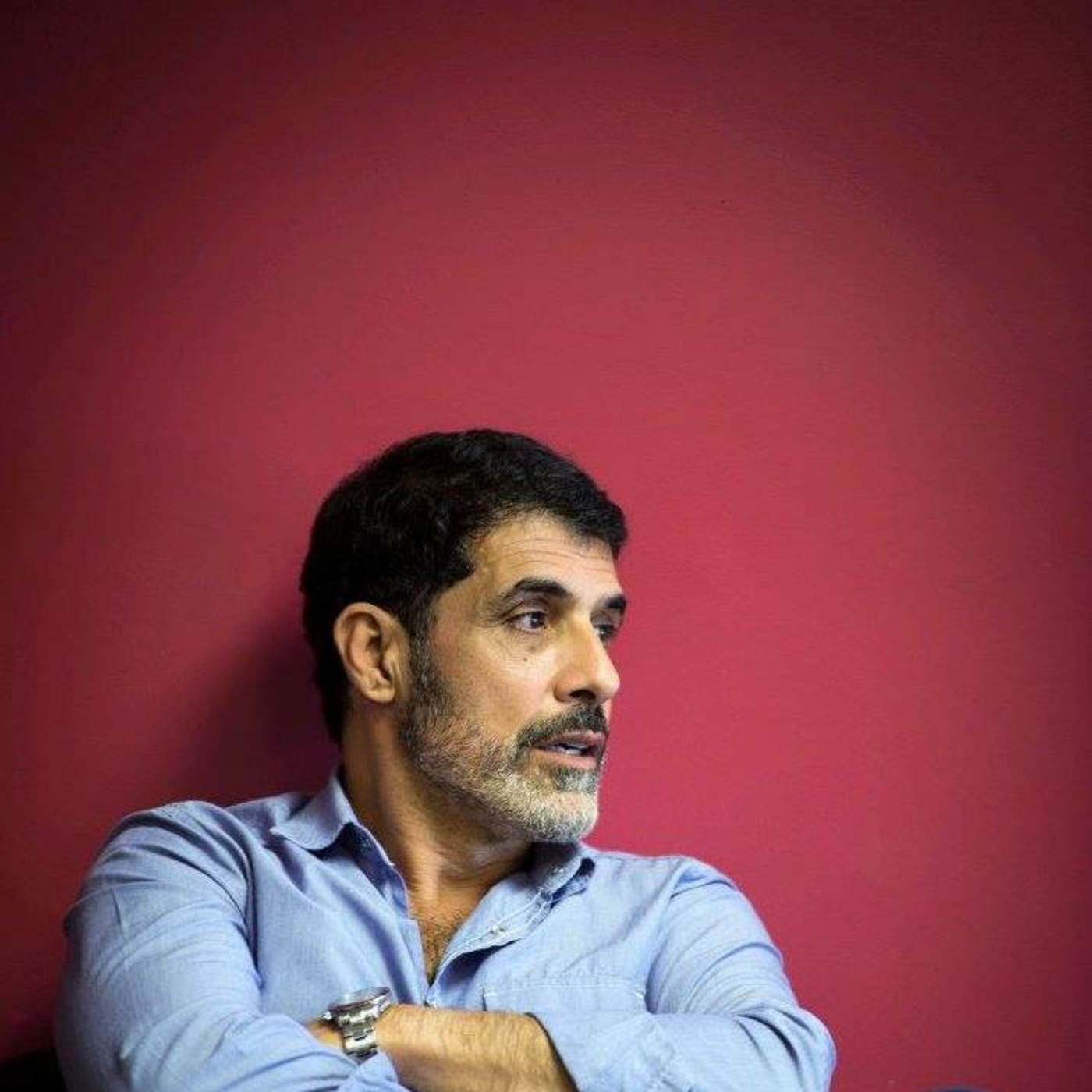

and when creatives in particular are constantly juggling survival work with their craft, UBI has gone from a fringe idea to a serious global conversation. And today I'm speaking with someone who's been in the center of that conversation for almost a decade. And he also happens to be an actor, Conrad Shaw. He is a researcher, producer, writer, and co-host of the Scott Santens UBI Enterprise podcast, which is where I found him, a podcast that I listen to.

He helped design and run one of the most ambitious basic income experiments ever created, the Bootstraps project, which we talk about giving everyday Americans a guaranteed income for over two years.

He's also the creator of the UBI calculator and co-founder of Comingle, a mutual aid platform built on basic income principles. But beyond all that Conrad brings a creative perspective, someone who knows firsthand the instability of the arts and the freedom that comes from removing the constant fear of financial precarity. So whether you're an actor, a creative or someone just trying to understand how society might work better.

This conversation is for you. Enjoy. And here we go.

David John Clark (02:03)

Good morning. Good evening. Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen, wherever you're coming from. We are back with the Late Bloomer Actor for season five. That's correct. I've said it, season five. I would like to welcome Conrad Shaw to the podcast for the Late Bloomer Actor. Morning, Conrad. How are you?

Conrad Shaw (02:20)

Good evening on my end of the world. I'm doing alright.

David John Clark (02:23)

Hey, where are you coming from today for everyone to know?

Conrad Shaw (02:26)

I'm in upstate New York. I was in New York City until the pandemic and then ended up a few hours north of New York City.

David John Clark (02:33)

Wonderful. Wonderful. I spent Christmas in New York about two years back now with the family and absolutely loved it except for the smell of marijuana from everyone smoking on the streets. But other than that, it's beautiful. Hey, I thought I might start season five off with something just a little bit different. Hence why you're here today. But it's certainly relevant to actors and something that I've been following with keen interest for a few years now. And that is UBI. Now I've got a bunch of people going UBI what? UBI.

Conrad Shaw (02:42)

Mm-hmm.

David John Clark (03:02)

Universal Basic Income. So before we deep dive into this topic though, could I ask you to give my audience a little background of yourself, your acting journey and how and or why you're now such a big advocate for the UBI concept.

Conrad Shaw (03:17)

Yeah, it's a weird journey. I came out of college with an engineering degree, but by the time I graduated, I sort of realized I wasn't super passionate about it. And also, I had taken an acting class like my senior year and realized, man, I have to at least try this. So I finished up my degree. I worked for a year doing engineering stuff.

Get it on my resume, make my parents feel better about my future. And then I dropped it all and I went to New York City to pursue acting, which I happened to choose a pretty bad time. I went in 2008 thinking like I could maybe make some money doing some finance stuff on the side, but nobody was hiring anybody. So I worked a lot of restaurants and just really struggled for a while getting going. Even took a couple of years before I could start taking classes.

David John Clark (03:45)

Yeah.

Conrad Shaw (04:09)

And I wanted to be an actor, a screenwriter, a filmmaker. And I was starting to cobble together the beginnings of a career, although it's incredibly difficult. I met my now wife, Deia, who was establishing herself as a documentarian. And we started clicking pretty well. To the degree we also knew we'd worked

together well and she wanted to do her next film, her first directorial debut and she asked if I would produce and I said, well, do you think I can handle that? And she said, yeah, I think you can, I'll help you. And so we were looking for a project for her and this was 2016 and I had read an article that just kind of came across my Facebook feed or something that said, what if we just gave people money?

And you know living in New York City being like sort of an engineering minded thinker and then trying to be an empathetic person like you walk by people who are in desperate need all the time and I and you don't really feel like a dollar is gonna do much and also you have no money and I wish there was like a really smart economies of scale way we could help all the people who need help, know, since we're not doing it We must just not have enough, you know for people.

David John Clark (05:18)

Mm.

Conrad Shaw (05:32)

And just going on about my business, you I got to pay the rent. I don't have time to solve the world's problems. And then this article kind of slaps me in the face and says, you know, we could just give everyone enough money to be basically okay. So I did some napkin math and like, convinced myself that at least the fundamentals were true. Like there's enough resources out there, at least in the US. I basically, you know, was working my restaurant jobs and hanging out with Deia my wife and

David John Clark (05:35)

Mmm.

Conrad Shaw (05:56)

I just wouldn't shut up about this idea because I just was picking everyone's brain about it. And one of the things that really appealed to me about it was like, this is back when Facebook, you could still talk to your friends and stuff. It was less awful. And my friend Mike comes along, and Mike is the guy who disagrees with me on everything all the time no matter what, magically somehow. And I'm like, here we go. Here comes the debate. The thing that really stuck out to me was in a couple of comments.

David John Clark (06:08)

Back.

Conrad Shaw (06:22)

Even Mike is like, yeah, I could see giving cash to families. And then it's just like, felt like for the first time, something I could plug into sort of semi politically that like felt like it had a future. And right at that time, Deia is looking for a project and she does like environmental, social justice, those sorts of films. And just kind of offhand one day after hearing me just talk about it too much again, she said, yeah, we could even ...

We could even make our project about UBI. And just sort of throwing it away. And then it kind of clicked like, no, that's actually a really interesting idea. Because it allowed us to tell stories of the kind that she wanted to. She was sick of big issue film documentaries where you drop in and tell a few stories about plastic pollution or whatever. She wanted to do longitudinal storytelling where you live with someone for a while. You get to know them as a person.

David John Clark (06:56)

Not.

Mm.

well.

Conrad Shaw (07:21)

And this sort of lent itself to a really interesting lens on how to get to know human beings. What does a human life look like in this alternate universe if you have a basic income? Which led us to a very ambitious sort of concept where we decided to try and put together a basic income program with people all across the country, which meant we had to raise a ton of money. We didn't know anybody with money, so it took a long time.

But the idea was to find a bunch of people from different walks of life getting a basic income and just film with them for a few years to answer that question that everyone has. Well, what do people do when you take absolute need out of the picture, when they don't have to work a job to get by? That was really my launching into the full-time work. was...

kind of being an instant geek about the idea and then having this great fortune to have met Deia and to have this project to dive into. So that led to 10 years of advocacy and work now that is culminating next year.

David John Clark (08:28)

Is that your Bootstraps project you're talking about there?

Conrad Shaw (08:31)

Yeah, that's series called Bootstraps and that's sort of a nod to both American mythology about meritocracy, like pull yourself up by your bootstraps. And there's a quote by Martin Luther King that references it too where he says, it is a cruel jest to say to a bootless man that he ought to pull himself up by his bootstraps. And so that's kind of where that came from. I don't know if it's common in Australia, but Americans ad nauseam

David John Clark (08:52)

Interesting.

Conrad Shaw (09:00)

will tell you to pull yourself up by your bootstraps. Like, do this in-

David John Clark (09:02)

It's a saying

I know, probably not something I've used before, but I certainly know the saying. So we'll certainly talk about that because I really want to dive into that project and what you got from that. But we want to talk about UBI and a little bit of focus, obviously, for creatives, because I know that it has been run out. I think it's being trialed in Ireland at the moment for creatives. So, but also is the bigger picture how it can help communities in general. But

For someone that's listening now, they're probably still going to basic income pay people that have no understanding of what we're talking about. So would you be able to just easily explain what the UBI concept is and how it works.

Conrad Shaw (09:45)

I've sort of come to simplifying it by breaking it down into the letters. And U is universal, so that means it goes to everybody. Meaning it's not like a targeted welfare program where it's like if you have too little money or something. Basically it goes to everybody. Basic means it's a baseline. A lot of people sort of think it means it's enough for basic needs. That's actually not.

David John Clark (09:55)

Hmm.

Conrad Shaw (10:06)

I encourage people not to think of it as the amount, but as like the mechanism. It's like you start at this income floor and everybody starts at this income floor. It's like a new zero. That's, you know, some amount of money and income means it's cash as in not like a voucher or some sort of, service or in kind aid. So essentially it's just like this contract we make as a society that says, you know what? Everyone has a starting salary for no matter what they do, essentially, like you have a regular

paycheck for the work of living and then what you do beyond that is up to you, right? There's still the labor market. They're still earning more money not a lot of people want to live on on the very bare necessities. The the big fear people have with a UBI is like does everyone just quit working and be lazy because now they don't have to and my take is that people don't want to just like stare at the wall and watch Netflix all day for the rest of their lives. People want to have vacations.

They want to have meaningful work in their lives. They want to feel like they're contributing to human history, you know. So I'm not as afraid of that as others.

David John Clark (11:12)

That's one that you sort of touched on there that people say, ⁓ you know, you're to pay people money and they're just going to not do anything. And how I got onto learning a lot more about UBI and finding you was through the podcast, the Scott Santens, the UBI Enterprise podcast, which explores the big ideas and data around UBI. Scott being a big advocate for UBI and you're a co-host on there. So one of the things that I

get a lot from that podcast is you talk a lot about how some of the trials of UBI have shown that that isn't the case when people are given a basic income. They don't go and sit on their asses as we like to say here in Australia and do nothing. Can you sort of dive into what benefits and the positive outcomes you've seen in some of the trials that have been run around the world? And if you can mention any of the trials, if you can remember off hand to go with that would be wonderful.

Conrad Shaw (12:06)

I mean, there's a ton of them. Like I ran one myself that was a small, like 11 households around the country. But there have been hundreds of pilots around the world of like different parameters, but kind of getting at this idea of direct cash that's unconditional. And you can spend it however you want from like large pilots in Africa that run by gift directly. There have been pilots in India, in the US, in Canada, and there's all over the place. You mentioned the one for artists.

David John Clark (12:08)

Hmm.

Conrad Shaw (12:35)

In Ireland, a lot of them have limitations that aren't like really fully universal basic income, obviously, because they're picking, 1000 people out of the country, which that's not universal. You can't get an idea of really the macroeconomic effects of something of that sort of policy. But what you can get a really good glimpse of is the human behavioral stuff, which is like what really drives people really motivates people. So for example, the Ireland artists one you mentioned,

they've had this program, I don't remember the exact details, Scott is the person who would be able to rattle off those numbers, but like, you know, a few thousand people in Ireland and basically you just have to report that you're working on art and you consider yourself an artist and you're eligible. They just made it permanent, I think, where every year they're going to do this again. ⁓

David John Clark (13:21)

Yeah, I think it's

starting in 2026 is what I read.

Conrad Shaw (13:24)

And they've done it in the past and what they found that was really interesting, well one is people work more on their art, obviously you have more time. Also people in general in these programs, whether artists or not, don't tend to work less. There's certain groups of people that might work less, like new moms or kids that need to go to school, but in general you find people work about the same or even more. You find that people are more engaged in their work because they're now working more for the right reasons.

I witnessed people having a more of an upward career trajectory when they were no longer so desperate to make money immediately when they lost a job or something. They could sort of hold out for a better job that turns into a career path and a more fulfilling way to contribute to society. So in general, you don't see it play out that people work less, that people create less or produce less. I mean, this is one of the questions I've wanted to answer

as a fundamental thing we're studying with our documentary and our basic income program is not just do people work less or more or like waste some of the money or whatever, acknowledging that all of the data from the hundreds of thousands of people who've been other pilots tends to show that the benefits are good, that people do continue to work and become more proactive. They, vices decline, people drink and do drugs less.

There's less domestic violence and all kinds of good outcomes. And the main thing that I've been trying to figure out is why, right? Like this comes to like the actor side of me in my training. It's like, what is really going on in the people? And how can I put myself in those shoes and try to understand, well, I don't have to go get a job. So what am I going to, why am going to go to a job? Right. And I was reading this book.

And I was witnessing in our own pilot, too, people just unleashed, really turning their lives around in inspiring ways. And I want to be a good skeptic and a good scientist. I was reading this book by David Graeber called Bullshit Jobs, the late David Graeber, some years ago. It's a brilliant book for a lot of reasons. But there was one chapter in particular that caught my attention.

Where he's describing a study in infant development, which is actually really relevant to me because I'm a new father myself, so I'm going to be watching for this that I'm about to tell you about. Thank you. Yeah, yeah. Thank you. So anyway, he describes this study, some German study about infant development where at around two to four months of age,

David John Clark (15:44)

Congratulations on that too. One month old little girl, wasn't it? Yeah, beautiful. Well done. Congratulations to you and your wife.

Conrad Shaw (16:03)

every single human being, according to this study, has this moment. And maybe you're like hanging out one day, this little baby doesn't really know what's going on, like sort of a passive entity in the world, your arms like kind of go around, you don't really control them, snot falls out of your face, all the things. And then one day your arm moves in a certain way and maybe like knocks your bottle over on the counter or the high chair. And for the first time, it sort of dawns on you

that like, wait a minute, did I knock the bottle over? Like, did I do that? Did I make that happen? And then you try to replicate it. Like you move your arm again and you knock it over and knock something else over. Your first like sort of realization happens that you can be a cause in the world, that you can do things to other things. You're not just a passive entity. You matter, right?

And for every single baby, according to this study anyway, that moment is just like pure elation. Like you're like, holy shit, you know, I did a thing, you know. And the theory that sort of emerges from that is that that is actually the most fundamental element of human nature from that day forward as we are all seeking that, what they call the joy of being a cause.

David John Clark (17:07)

Yeah.

Mm.

Conrad Shaw (17:23)

Meaning

we want to write the stories of our own lives, we want to matter, we want to leave a legacy. So this whole we're going to sit around and pick our nose and watch TV because now we're comfortable enough to do that, falls apart when you understand what really drives people, which is not comfort seeking, it's purpose seeking. And that sort of helped coalesce why I think a UBI world has so much potential, because it unleashes that deeper human nature, which is purpose seeking.

Whereas sort of this scarcity world we live in, says, you know, fight against each other for the right to live, kind of turns us into our lesser selves where we have to think about how much we can take for ourselves so that we don't suffer like very physical and existential insecurity. If you're sort of a caged animal, you're backed against the wall, you're not allowed to think about your higher self. You have to just...

try to figure how to get food to yourself and your kids every day. So the big philosophical question for me that is very relevant to art is when we no longer have to think about how much we want to take for ourselves or have to take for ourselves and we can think about what we want to be and what we want to give, what does that look like for the human species and the arts especially?

David John Clark (18:22)

Mmm.

Yeah, I want to dive into the benefits for artists and actors. I just wanted to touch on a point there that you said a couple of times with the child realized that they matter. That, that to me is immense. That's huge that we live in a society now where I think a lot of people don't think that they matter. And that's where the homelessness comes from and the drug addiction, the alcoholism and the

their criminality, perhaps because people no longer think that they, anyone cares about them and that they don't matter. So that's huge to me, just that, that little point that you made about us mattering about that, that, that's how much it changes people. Is that what you're seeing in the UBI and the positives of that? Because how, how much would that change a society if we could turn just even half the people or 25 % of the people who don't give a shit about their lives into that thought process of I matter.

Those two words.

Conrad Shaw (19:39)

I mean, there's no simpler way to validate someone and to let them know that you matter than to invest in them, to put your money where your mouth is. And as a society, if we're saying, we believe in you enough to invest in you, these resources without question, without conditions, we think that you have potential and we're going to let you pursue that potential and we're not going to tell you how to do it. That is like saying, not only you matter, but...

David John Clark (19:49)

Mmm.

Conrad Shaw (20:08)

We love you and believe in you. And not everyone's going to live up perfectly to that expectation. But I think you do find in general that people do live up to the expectations you give. So if you treat everyone like a criminal, you'll get a lot more criminality. If you treat everyone like an upstanding citizen and you accompany encouragement, support, expectation, accountability, people will step up.

David John Clark (20:24)

Mm.

Conrad Shaw (20:34)

to that level.

David John Clark (20:36)

Hmm. It's funny how you talk about that. I work in a job that I don't mention on social media, but I get to talk to a lot of people in certain aspects of their lives in a criminal sort of sense. And, I, I have that approach and I talk to people how I want to be talked to and I give them the respect I let if, if they want to play a card and, and, come across in the wrong way, then I'll change my aspect. But it's amazing how many times when I give someone the respect,

of their personality or their person in their life that they come across so much different because it's you immediately get that respect. And I can see the benefits of that how this is such an encompassing thing that can just change society. And we haven't even touched on why we're here today and talk about actors. That's brilliant.

Conrad Shaw (21:22)

Yeah,

I mean, I believe, acting gets to the heart of like purpose and character and what are you here on this earth for? I think the most important thing you can tell someone is that you matter. And when you look at, so when people say, come on, man, there's lazy people, there's greedy people, there's drug addicts, there's whatever, all over this world. How do you account for that? And I basically suggest that if you train yourself to look at everybody you ever witness and

and make the assumption that they are coming from this place of wanting to matter, like that is their primary driver, then self-destructive behaviors and things like that. What explains that? Your ability to pursue the mattering that is important to you has been taken from you, has been squashed. Like these behaviors, drug addiction and self-destructive behaviors are escapist behaviors.

David John Clark (22:17)

Definitely.

Conrad Shaw (22:17)

We all have

our own ones. I kind of clock out and I'll drink more or I'll eat more chocolate or something or I'll play too many games on my computer when I just don't know what the hell to do with my life and I feel sort of squashed and paralyzed. And we have a society that says the only way you're allowed to exist for a lot of people is to just march to these orders and do these things and work. There's no what do you want to do with your life question.

Unless you're lucky enough to be in one of the upper echelons of society. So I would love to see what it looks like when everyone has sort of the freedom to really ask themselves what matters to them and pursue it.

David John Clark (22:58)

That's interesting. And I've got so many questions coming to my head now, which is taking us deep diving into UBI that is obviously a whole another show in itself. As an actor yourself, what do you think most creatives might misunderstand about the potential impact of UBI on their careers? You know, read things about their mental health and things like their ability to take risks and to push their career forward. How do you see that being a good thing for actors?

Conrad Shaw (23:25)

I I would just encourage everyone to imagine a basic income, $1,000 a month, whatever it is, and assume it's in place, and then game out your own situation. What would I do if this was true? What would I spend it on? What would I have done the last 10 years? And for me, I know very clearly what I would have done. I wouldn't have spent an extra 10 years working just in restaurants waiting to start. Like, keep biting my lip when my family would be like,

So how long are you gonna give this a shot for before you give up? And it's like, I don't know, ask me when I feel like I've started. It's just crushing, it's soul crushing. It's not for everyone, the arts or acting. They say you gotta want it, you gotta need it. But also you gotta be able to give it a shot before you can give it up, right? So I felt like one of a million waiting to be...

actors are waiting to be aspiring actors waiting tables, you know, it's funny. They call it waiting and If I had had a basic income getting out of college, this is not to besmirch restaurant work, by the way, I got a lot out of that. It just wasn't like my calling It wasn't what I wanted to do. And I knew what I wanted to do. So every day I go into work, six out of eight hours

David John Clark (24:32)

Of course.

Conrad Shaw (24:42)

are lost toward keeping a roof over my head so I can come back to work again. It's cyclical. It's depressing. If there was a basic income of $1,000 a month, I lived on about $1,000 a month in New York City for a long time. Not comfortably. I had tons of roommates. But if we had a basic income, those roommates would have been three of my acting buddies from school. And it would have covered our entire rent. Or maybe I would have worked 10 hours a week.

And we would have been making plays, we'd have been making short films, we'd have been writing, we'd been giving it the real try, rather than going through the way they tell you to try, which is like, well, work your ass off at some other job for a long, time. And then maybe in your spare time, you'll get a big break if you apply to enough commercial auditions for 15 years. And it's like, it just completely squashes all of the art inside of you. So yeah.

I actually on.

David John Clark (25:38)

Well, it would

give you more opportunities, wouldn't it? So many times when you are having to work a nine to five job or work shift work in a restaurant or whatever, you're actually missing opportunities. So that stretches that period of becoming a successful actor out a lot longer, wouldn't it?

Conrad Shaw (25:54)

Yeah, and your energy is

so tired, torn, like you can't devote it to a craft like you should. I mean, if you ever notice, like the people who, by and large, make it in the arts, especially acting, came from a position of enough comfort that they didn't have to pay their rent for five years or something like that. Like they could really kind of go at it full time. Whereas the people who did it, in 10 hours a week in between their shifts, getting their big break is a story people love to tell, but it doesn't happen as much. It's usually...

connections and freedom that allow people to become artists because they can really pursue their craft.

David John Clark (26:28)

Yeah, I love that.

Conrad Shaw (26:30)

And take investments, like

entrepreneurial risk, like writing a show and putting it up. And it takes a lot of the ability to risk, as well as all of the people that you're asking to kind of do it with you. I remember putting together short films and asking all my buddies to do it with me, and even paying him a little bit sometimes if I could raise the money or just wanted to go into debt. But you're always beholden to, did they get another job? Did they get another gig?

David John Clark (26:33)

Mmm.

Conrad Shaw (27:00)

You're last on the totem pole. And so you can't really put together good stuff. You can't put together a good community show because everyone else first and foremost has to pay their rent.

David John Clark (27:11)

It just changes everything. And I think you used the word before, gives you that base level, hence the term basic, to be able to do something. And a lot of people say, well, if we have a basic income, we're not going to have cleaners anymore. We've been talking about waiters and that. I said, well, that's not correct either, because how many people do we know that work two jobs to make ends meet? So if you've got a single mom who's trying to look after her children and stuff, so she'll work a cleaning job by day and a

another cleaning job by night, a basic income would now give her that opportunity to say, I only need to do the one job. I can focus more on my children. And then the benefits of that, mum's home. So the kids aren't out on the street. Their kids aren't committing crimes. They're not going down the same path as everyone else in their neighborhood. It's just, it's just so many positives that you can see straight away.

Conrad Shaw (27:59)

Well,

on the whole, who's going to do the unpleasant jobs? Like, who's going to clean my toilet? Comment. Like, we hear it a lot. it's like, it belies, it's kind of almost saying the quiet part out loud. You think these jobs are so unpleasant that someone has to be forced to do it against their will. But in a world with UBI, say that person is getting $1,000 a month. Maybe they won't do, maybe they won't clean your toilets for starvation wages.

David John Clark (28:15)

Mmm.

Conrad Shaw (28:25)

Because they don't absolutely need it and aren't totally desperate for it, maybe you have to pay them what that job is actually worth, and you can't extort them into doing this unpleasant labor. So I do imagine in a world with a UBI, then certain jobs would pay, like you'd have a rebalancing of what pays what, you know, and a janitorial dirty job that isn't as pleasant to people might have to pay more, and a job that people find really fulfilling might pay less.

David John Clark (28:41)

Mm.

Conrad Shaw (28:52)

In the acting world, I think about how hard it was to put up a community theater show because there are all these rules and regulations meant to protect actors, saying you have to pay a certain amount of wage or whatever. But that in turn meant only certain level establishments could put on plays at all. Otherwise, if you don't have the money, you're not even allowed to play because you'd be like an extortive boss or something. Even if it's you and your friends just trying to put something up. But if everything becomes voluntary and people can really

take the fulfilling the fulfilling this of the job as part of their pay because they're not going to go starve, then all of a sudden we have a more free and competitive market for the labor market where the desirable jobs have high competition and people willing to work less for it and the undesirable jobs have to pay more for what they're worth and any in any job negotiation the person on the employee side

has the right amount of leverage. They don't have to say yes to something. And so they're not beholden to the desperation in the market. When you go look for a job, it doesn't have to be in the arts, it can be anywhere. Usually in the modern world, you're paid as much as they can get away, or as little as they can get away with paying you. If someone's going to come and take that job for less,

then that's how much the job's gonna go for. It's not based on how much you're worth. Like, I remember as an engineer, they were giving me 30 bucks an hour out of college and charging 150 bucks an hour. They weren't spending 120 on overhead. They were spending on the fact that I would take 30, you know?

David John Clark (30:19)

course.

Hmm. And I was going to say just before, one of the biggest things there is that it gives you the ability to take risks a bit more, doesn't I think we've touched on a little bit there. So you were saying the community show, putting on a community theater show costs money to put it together. And if you don't see that you might not make a profit at the end, you just can't do it. So that's why you don't. But if you've got that ability, you're still feeding yourself, you take that chance now, and then all of a sudden,

you've just put on this show and every, you've got a full house every night and you've walked away with a profit or you've put together a small TV series. You've got your acting friends together. You've put a bundled, bit of money. You've done it on the cheap and you've made it run. And then because you've taken that risk, now you've got the next Breaking Bad. ⁓ That's a positive.

Conrad Shaw (31:23)

Well, and you've created something

awesome for society, right? The great art doesn't come out of these gigantic networks who are trying to think of their bottom line with their algorithms. It comes out of the groundbreaking artists. Breaking Bad is a great example. It's one of those things that, in retrospect, it's of course, that kind of show was going to make it, was going to have a big impact. But

just like every other great groundbreaking show, they have a story of how it took a decade to get anyone with money to allow them to make that show. A lot of people when it comes to basic income, they focus very heavily on the power to end poverty, right? Because we're so focused on poverty as the end all be all ill. And don't get me wrong, essentially a basic income would abolish poverty, and that would be world changing.

It was just a mathematical way to say no one's below this poverty line. However, I think an even bigger deal is the unleashing of people by giving them that risk tolerance. Because if you think about how many millions and billions of people are walking around in our countries and in this planet, like with big ideas, with passion, with aspirations, but

David John Clark (32:11)

⁓

Conrad Shaw (32:39)

putting it off indefinitely, probably never to get to it because first and foremost, they have to make sure they're okay, that they're safe, that their kids are safe, right? And what ends up happening is we only get to see the great innovations and things from the people who had enough financial support and security or just blind stubbornness and luck to pull it off. In terms of human flourishing, I feel like...

David John Clark (33:01)

Mm.

Conrad Shaw (33:06)

If we give everyone in society the ability to pursue that dream and the consequence of failure, not being abject poverty, sure, we'll get a lot more crappy art and bad ideas, and we'll get a lot more great art and amazing world-changing ideas. I think we'll just sort of unleash humanity itself.

David John Clark (33:23)

Mm.

It's interesting because if you look at, for an example, I was just thinking then of drug makers, the only impetus to go forward to make drugs is to make money. So the only research going into the drug market is what drugs can we develop to manage someone's condition? That's where the investment goes because then they know at the end of it, if we spend a hundred million dollars on this research, we'll come up with a pill that can manage someone's condition.

And then they've got to pay us a hundred bucks a month to do to manage that condition and we make a profit. But why would you invest into a doctor who says I can cure this condition because they don't make any money once that condition is cured. So it puts that, that ability of people to say, I know what I want to accomplish here and they'll do it. That's Is that a good way of looking at it?

Conrad Shaw (34:04)

Mm-hmm.

Yeah, there's a whole moral reframing too of like, the capitalism, socialism forever debate is always at odds. And what's sort of unfortunate is that it's so often gets spun as like, it's one or the other. Like there is such a thing as either pure form of a thing, like pure capitalism or pure socialism, but pure socialism is just as naive as pure capitalism. Pure capitalism looks like, you know, eventually

David John Clark (34:18)

Mmm.

Conrad Shaw (34:43)

Jeff Bezos or Elon Musk just owns all of us. And pure socialism sort of squashes individuality and innovation. And the way to look at it that I think is the way to look at it as an engineer and a former design engineer is it's an ever-evolving design. And we want both elements. We want capitalistic policies and mechanisms where we want to incentivize people and motivate people and give people bigger rewards for working harder.

But we also want socialist mechanisms, socialistic mechanisms, where we want protections. Because if you don't have certain protections in place, you end up getting corrupt and manipulative markets and extortion and monopoly. And you end up with people who are insecure enough that they have to turn to crime. And everything breaks down when you don't have socialistic things like fire department, police, libraries, health care.

David John Clark (35:35)

Mmm, of course.

Conrad Shaw (35:36)

This is just one of those things where if we decided that one of the protections and or bolstering sort of policies we want to have for people is a certain amount of cash, then that would be on that end of the spectrum. It's not like embrace socialism. It's like embrace this much social protection for everybody so that capitalism can actually function.

You know, like the markets, right, like they have to play off of each other in a realistic view of a society.

David John Clark (36:01)

Take the positives from both sides, so to speak.

Going down a little bit of a dark tunnel, then a lot of people might feel that this could never happen because would the government lose control of the people? A lot of talk about how the governments want to control people and again, it comes to money. It's these upper echelons of people controlling the government through their money because they want that control. But if we start giving everyone the income and getting the positives that we've talked about already today, is that

losing a little bit of that control of the people because now they have their own word, they have their own direction and they want more.

Conrad Shaw (36:45)

Yeah.

Yeah, the government has, in this paradigm where it's a true UBI, it is, there is less of an ability to control people. And that was actually, you were gonna ask me about a quote. One of the ones I came up with was it's just like a sort of an equation where money is power and UBI is money to the people.

Any questions? Right? And it's funny because you have a lot of people whose reaction at this time, there's been a lot of spin that's ⁓ UBI is just some sort of a Trojan horse to make us dependent on the government. And so the government can control us and tell us what to do because if you don't do what they say, we'll take away your UBI. It's a very fundamental misunderstanding of what UBI is. If that's what it was, it wouldn't be UBI. It would be conditional

David John Clark (37:13)

100 questions.

Conrad Shaw (37:37)

welfare, right? In which case, yeah, that is a problem. And it's a problem we already have. You have to toe the line in order to get the conditional supports. But if it's an unconditional support, if it's a right, it's a dividend, it's your part ownership in the resources of the country that you get without question, codified into the Bill of Rights or something like that, then absolutely, it does transfer. It's a major shift in the power dynamics.

David John Clark (37:39)

Mmm.

Conrad Shaw (38:05)

When it really starts happening, yeah, I can see the big national and global forces fighting pretty hard against it. People of wealth who aren't going to be able to buy their way around anything.

David John Clark (38:17)

Which is what's happening so much more these days. And talking about money and we haven't discussed it. And this is a question that will come up straight away is where does the money come from? So if we're going to pay a UBI, we're talking, you know, how many hundreds of millions of people in America, how many millions of people in Australia, if we just pay every single person above the age of 18 a certain amount, whether that's 300 a month, a thousand a month or equivalent to the age pension, for example, which I think is in Australia is

28 to $32,000 a year, would to me would be what I would consider enough to be able to pay your rent and have a decent life. Where's that money come from?

Conrad Shaw (38:57)

Yeah, there's so short answers. There's lots of ways. And I'll start with the napkin math, which is I looked at when I was when I was first assaulted by that idea that we could just give people money. It's like, well, then why aren't we? So I looked up in the US back in 2016, the per capita average income. And it was something like 55 or $60,000 a year. And this is including everybody like people of working age, kids, retirees, disabled, whatever.

And then per capita wealth was something about like 240,000 or something and it's all gone up since then but I looked at that and I said so the average household of four is is bringing in you know over 200 grand and has a million dollars in the bank that doesn't and that's the average and it's like oh so we have enough to give everyone $12,000 a year and have like several times over and still have

David John Clark (39:36)

Of course.

All right.

Conrad Shaw (39:55)

plenty left over to be the inequality fund, if you will, to still have billionaires and stuff like that. At a basic level, the resources are there. Money represents resources, food, shelter, opportunities, services. So it's a question of, can we distribute it in a better way and not have it so limited to some people and so hoarded by others? Now, the question of how do you actually do that?

One thing to reiterate here is I very specifically call it a baseline rather than a basic income because a lot of people assume that it's extra money for everybody. Why would we give that to Bill Gates? He doesn't need it. And that's missing that a smart basic income would be coupled with taxation. It's essentially a redistributive policy. If you do it intelligently, which is

you start everyone at that floor and then taxes are a little higher on each dollar so that it ends up largely paying itself back. There's a break-even point if we have an extra 10 % income tax. I'm starting out with 15 grand in basic income. When I make 150,000 in earnings, I will have paid it back in broken even. And when I make a million dollars, I will have paid several other people's basic incomes. And so this becomes just a...

a smarter way to make sure, to sort of give a pre-bate to everybody, a tax credit in advance to everyone to give you some spending money to show up in the marketplace. But you could pay for it through different forms of taxation. You could also do some of it through money creation, deficit spending, but you don't have to. And in seeking out what are the actual economics behind this? Because I was really kind of sensing that

nobody, including my fellow advocates, really knew what they were talking about with the economics in the US. I spent a year building a thing called the UBI calculator. So if you want to look up ubicalculator.com, it's got a bunch of different possible ways that it analyzes to fund the basic income. And it tries to be super conservative, make it look as bad as possible. And analyzes a bunch of policies, including Andrew Yang's, who was running at the time, who's running for president on UBI.

David John Clark (41:55)

Nice, okay.

Conrad Shaw (42:02)

Just to convince myself, yeah, there's a ton of ways we could do this, and they have different sort of values behind them. Do we fund it with a carbon tax? Do we fund it with land value tax? Do we fund it with whatever? And I didn't make it fully robust, but the whole point was to show myself and learn from myself and others, that there are a lot of ways to do this, that the devil is in the details. For each one in the calculator, you can see what percentage of Americans would have come out ahead

under that policy. And it's different for each one. Is the breakeven point at 50,000 or 100,000? It just kind of depends how you set it up. And I'm less concerned with how you'd pay for it. Eventually, I want to upgrade that calculator to let people sort of design and submit their own ideas for upvoting. For me, if it's direct cash going to the people, I don't really care where the money comes from. I think it's a good way to

David John Clark (42:29)

OK.

Conrad Shaw (42:54)

to use it rather than letting a government office have a say in how it gets spent. Just make every citizen their own little government office with a certain amount of money.

David John Clark (43:00)

Hmm.

And you've, you've got a video you sent a link to me and I'll put it in the show notes. I think you put it out during the actor strike because it's titled how to win a strike every time. But you go through that there's a nice little graph in there that shows the little cut off the top of each person towards a UBI. And that graph goes up to someone earning 150,000 and then more. And I think there were numbers there from memory, something like 7%. So if you're earning a million dollars a year, and we take 7 % off you

to fund a UBI, please tell me that that's not going to upset you because 7 % is not a lot of money. And so that's, yeah, and I talk about this a lot when we talk about AI taking over our jobs. A local shopping center, we have a Woolworths here in Australia. You've got Walmart and stuff like that. So we used to have 10 checkout chicks, you know, at the checkout. So you'd go through, or checkout blokes, come on. And

Conrad Shaw (43:42)

And you'll have a lot more customers for your business ⁓ if that happens.

David John Clark (44:03)

But now we don't, now we've got computer terminals. there's 10 jobs gone Yet, these shops, these stores are still making the same profit, if not more, because they're not paying that income. So where's that money going? That money is now going into the coffers for that company, which goes to the shareholders, which a majority of shareholders are richer people. Okay. So we have our retirement monies in shares, superannuation here in Australia. So it does

filter down to us, but the end of the day, all of a sudden we don't have people working for these companies yet they are still customers. But if they don't have an income, they will no longer become a customer and the big business will run out. Whereas if we just tax the companies at a better rate and put that into the UBI system, that's where the money comes from. That's how I've been looking at it. Am I on the mark there?

Conrad Shaw (44:58)

Yeah, I think it's not only the moral thing to do, but it's the smartest thing to do advantageously. Henry Ford, at one point, started paying his employees more because he realized he needed people in society to have enough money to buy his cars. It's kind of like that. Right now, there's a lot more growing pressure for things like AI dividends. If all of this extra money is coming,

David John Clark (45:03)

Hmm.

Hmm.

Conrad Shaw (45:23)

and it's not like the, the siphoning of productivity from the workers to the, the owners, the shareholders is new. It's been going on, you know, like $80 trillion have been siphoned in the last 50 years in America from the everyone to the, to the 1 % essentially, but it's been happening slow. Like the frog in the pot of water that's slowly getting turned up to boiling metaphor thing. But now AI is like this.

It's such a rapid thing. It's harder for people to dismiss like, like, yeah, we've always lost jobs. We'll always bounce back. We think we can't predict it. It's like the, you know, the pushes come in the shove soon. And it's like, you can't keep saying that when, know, these reports are coming out, like, 25 % of jobs are going to get displaced in the next three years. And all the kids coming out of school are finding that they can't, they can't get entry level positions.

It doesn't take a lot of visionary foresight to see that the labor market is maybe no longer going to do what it always did for us, which was serve as the primary and only mechanism for most people to get their money. And if it fails us as that mechanism and becomes at best like a way for some people to get their money, then we need another mechanism for everybody to get some money or society collapses.

David John Clark (46:29)

Hmm.

Mm.

Conrad Shaw (46:46)

it's coming to a head in the near future if we don't do something about it, if the trends keep going the way they're going.

David John Clark (46:52)

Yeah, it's that gap between the haves and the have nots as they say is getting bigger and bigger. And I always say, it's huge in America for you guys, a sports person, your footballers are earning, how much do they earn? Hundreds of millions or millions and millions of dollars to kick a football. and, and, okay, let's look at actors ourselves. Tom Cruise, a wonderful actor and he deserves every dollar they give him, but a hundred million dollars to make a movie. Who needs that much money? How much money is, is too much, but

Conrad Shaw (47:05)

yeah, I don't know.

David John Clark (47:21)

We don't need to curtail how much money people can make. If you want to become the big actor or the big investor or whatever, you still can, but contribute a little bit more to society so that trickle down effect is more than what it is now.

Conrad Shaw (47:34)

Well, what you sort of referenced that video that you're going to share the link to is about another project of ours. I sort of tapped into the engineering side of me, starting in 2020. And the 7 % isn't necessarily the amount of taxation for what a UBI is. I want people to walk away with that. That's the amount that we're building into this web platform that we're building to actually

develop a UBI. To have a UBI that's done in the private sector just as a voluntary, almost like a social media platform whose sole purpose is to connect people's finances and create this UBI floor for everybody. And it is its own, like, basically a 7 % tax slash tithe on everybody's money that we all throw into a pool and it goes right back out to everybody. So anyone who's below the average income of the group, which is like two-thirds, would come out ahead and you come out further ahead, depending on how far down you are

in your income for that given week. And we're building this to sort of, well, do an end run around the whole political thing of like trying to convince everybody that this is a good idea to try something so radical and new and just see of the people who are interested in trying, like how many people just want to try it with us? We have the power of the internet. Maybe we can do this for 10 million people and just show essentially a little nation of people that are making UBI work.

David John Clark (48:58)

Wow. And that's, Comingle? Is that what you're talking about now? Yeah. All right. I'll certainly put a link into that. people, cause obviously that's a whole nother hour to talk about that as well, but that sort of goes into what we've been talking about.

Conrad Shaw (49:01)

Yeah, Comingle.

But that

ties into that video because in that video I'm positioning Comingle as one of the zillion ways you could use it if you're really just connecting people's finances and their power together in a very elegant way and an efficient way. One of the ideas was it's a way to, in a disaster situation, get disaster aid to people or in a strike situation, get strike funds to people. So I was positing like...

David John Clark (49:24)

Hmm.

Conrad Shaw (49:38)

All this money went to the SAG-AFTRA Foundation and things like that. And it comes from people like Tom Cruise or The Rock. You see these million dollar or ten million dollar donations for the actors. But then if you dig into the finances of these foundations years later, they're not set up for direct cash transfers to people. They're set up for very conditional, very

programmatic stuff and looking into it it's like okay you've got 11 million dollars that year for all these actors and 1 million went to them and 6 million went to your own staff and 4 million went to your endowment or whatever and it's like what we're talking about setting up which is actually part of the plan there is when we're rolled out to use such situations to to allow these big figure donors to have a much splashier

donation knowing that every penny is going to people on there's receiving it so The Rock or whatever Ryan Reynolds could have given that million dollars to that fund knowing that over the next week or three or whatever it would have gone 100 % to other actors. This idea that if Tom Cruise doesn't need to make a hundred million dollars for a film if he signed up to this thing where it's yeah well, I know that

10 % is going to my agent, 10 % is going to my manager, and 10 % is going back to the community of actors or my fellow Americans. And I didn't have to think about it. It's just going to get redistributed to everybody. And I know I'm doing my part. Great. That's what we want to build.

David John Clark (51:11)

Love it. I love it. Well, we could continue on this path for hours and I can see your passion in there. That's what I've been seeing with the UBI. I've talked about it on my podcast a couple of times. Tiffany Lyndall-Knight, who's a member of our union here in Australia was on my show and she was into it as well. So it's nice to see that the unions are looking at it. To wind up.

Firstly, I just want to thank you again. It's been extremely enlightening and hopefully an eye-opener for my listeners into the possibilities that UBI, both for creatives and communities in general, how positive that can be. Is there anything pertinent that we may have missed in our discussion you'd like to quickly address or throw out there before we wind up?

Conrad Shaw (51:52)

I think if the idea landed well enough that it's basically unconditional money and freedom and people just understand the mechanism and kind of walk around their lives with this understanding and just kind of let it play on their imagination. What would I do? What would that person do? Whatever. And maybe also take away that like what if everyone really does just want to matter, want to know that they're like

they're on this planet for a reason that they're deciding to write their own story, not just doing what they're told. If you kind of just embrace those a little bit or consider those as you go out in the world, think this idea will kind of grow in you like it grows in everybody, I think. It just makes sense. Yeah. ⁓

David John Clark (52:37)

Hmm. Beautiful.

And just before I ask my last question, I meant to mention it before when you're talking about a child knocking the cup over and, realizing they mattered and that they had that causality to do something. Just quickly, it made me think about AI, where AI is going. Wouldn't AI think the same thing when it realizes it caused something to happen? Does it, does it not work the same way as to

Conrad Shaw (53:01)

interesting thought.

David John Clark (53:04)

two month old baby girl that you've got at home when she realizes I've knocked over a cup I can do something.

Conrad Shaw (53:09)

My, I mean, that can be scary or that can be exciting. I've always wanted to see, I've always wanted to see the utopian versions of that, which is why Her is one of my favorite movies. It's just such a brilliant take on sort of the AI becoming self-aware situation, or it's like through a love story. Yeah. ⁓

David John Clark (53:15)

Mmm.

Whereas I watch Terminator,

see Terminator is all mine. The other end of the aspect. ⁓

Conrad Shaw (53:35)

Like, I never understood

why if something becomes hyper intelligent, why would it necessarily want to kill us? It might just be like, that's cute, and we'd be pets, and that could be great. Like, maybe, like I take good care of my pets.

David John Clark (53:50)

Hmm,

definitely. Maybe it's we always called the negative side of us human nature. It's human nature. So maybe computers have that same thing in the background. That's another whole show in itself. Conrad, thank you very much. My final question for you on a lighter note that I like to ask most of my guests is what would your t-shirt quote be? So if you put something on a t-shirt and you're willing to walk out in public with it, what would your quote be?

Conrad Shaw (54:16)

I've got two answers, one's cheekier. The first one is just a plug for me and Scott's foundation. And we're going to start doing merch with it. But the foundation is called Income to Support All Foundation, which the acronym is ITSA. So like, what is UBI? It's a foundation, like in your life and society. So the merch on the shirt would say, it's a shirt. And then people have to ask you about it. ⁓ My real quote, my real quote is,

David John Clark (54:30)

It's up, yep.

I love that.

Nice, I like that.

Conrad Shaw (54:45)

I believe in UBI because I believe in you.

David John Clark (54:49)

Nice. I'll buy that shirt. Thank you very much, Conrad. This has been an absolute pleasure. As I said, something a bit different for my podcast, but to bring it back to the late bloomer and late bloomer actors, we can see how many actors they start off young, they come out of college or they want to be an actor, but then they decide they can't do it. They've got to, they've got to pay their bills. They've got to have a career. So they give up on their dream

to go and get their job and to get their career. And they come back into the acting later in life in their 40s or 50s when they're in a position financially to be able to do it. And perhaps the term late bloomer will disappear because people might have that opportunity to follow their dreams earlier.

So thank you very much. It's been an absolute pleasure talking to you today and hopefully I'll see you on set sometime.

Conrad Shaw (55:42)

Yeah, I hope so. Yeah, give me call when you're casting.

David John Clark (55:47)

Thank you. And I'll put everything in the show notes, links to your pages and certainly your background, UBI and ITSA etc. So people can start to look it up. The more people that are interested in the more people that start looking into these areas, the more chance that it might become something in the very near future. Thank you very much, Conrad.

Conrad Shaw (56:06)

Thank you.

David John Clark (56:09)

Well, there you go, ladies and gentlemen, UBI. I'm hoping that at the end of that episode, you have a bigger and a better understanding of what UBI is and

and how it can benefit not only creators, but just the general society itself. A massive thank you to Conrad Shaw for sharing not just the research and data behind UBI, but the human stories, the lived experiences and what this idea could mean for creatives around the world. When we talk about universal basic income, we're talking about something deeper. The freedom to create, the freedom to explore, the freedom to build a life that isn't dictated entirely by financial fear. For artists,

and actors, late bloomers like myself, and anyone who's ever felt the pressures of the gig economy. A UBI isn't about replacing work, it's about giving work and creativity a genuine chance to flourish. If today's conversations sparked something in you, I encourage you to check out Conrad's work on the Bootstraps project, the UBI calculator, the mutual aid platform, Comingle, and of course his podcast, the Scott Santens UBI Enterprise that he's a co-host with, with obviously Scott Santens, who

is the man that knows all about UBI. It's fantastic to listen to. The links will be in the show notes. What I wanted to do quickly is to sort of, what did I get? What out of UBI? What is it? Well, universal basic income is a system where every adult receives a regular unconditional cash payment. No strings attached. It's not welfare. It's not means tested. And it doesn't disappear when you get a job. It's simply a financial flaw. And that's what we talked about in the episode that

baseline level security that everyone can stand on. The idea is that when people aren't living in constant economic stress, they can make better decisions, take healthier risks and contribute more to their communities and build more stable lives. And for creatives, actors, writers, filmmakers, musicians whose incomes can be unpredictable, at the best of times, UBI could mean the difference between burnout and being able to fully explore your craft.

Think of it as income stability in an unstable world. And that world is just feels like it's more and more unstable every day. So it's a foundation that lets people build instead of just survive. So that's what I got out of it. I hope you get something out of it as well. Thank you very much for joining me this month. And we're at the start of season five, a new year. I've got some great ideas coming for you for every month for this year. please join me along the ride. And if you've got anything to say

reach out and let me know who you'd like to talk on the podcast or what you would like to talk about. Thank you very much guys. See you on set.

Podcasts we love

Check out these other fine podcasts recommended by us, not an algorithm.

The Real Life Actor

Jeff Seymour

Audrey Helps Actors Podcast

Audrey Moore

Tipsy Casting

Jessica Sherman and Jenn Presser

Castability: The Podcast

The Castability App

Wendy Alane Wright's Secrets of a Hollywood Talent Manager Podcast

Wendy Alane Wright

Think Bigger Actors Podcast

DaJuan Johnson

ACTORS! YOU ARE ENOUGH!!

Amy Lyndon

Act Bold - Where Talent Meets A Plan

Act Bold with Anne Alexander-Sieder

An Actor Survives

Emily McKnight

Podnews Weekly Review

James Cridland and Sam Sethi

Buzzcast

Buzzsprout

Box Angeles (for Actors)

Mike 'Box' Elder

Brian Breaks Character

Brian Patacca

Celebrity Catch Up: Life After That Thing I Did

Genevieve HassanCinema Australia

Cinema Australia

Don't Be So Dramatic

Rachel BakerEquity Foundation Podcast

Equity Foundation PodcastIn The Moment: Acting, Art and Life

Anthony MeindlIn the Envelope: The Actor’s Podcast

Backstage

Inside of You with Michael Rosenbaum

Cumulus Podcast Network

Inspired by Nick Jones

Nick Jones

Killer Casting

Lisa Zambetti, Dean Laffan

Literally! With Rob Lowe

Stitcher & Team Coco, Rob Lowe

Need To Know

Bryce Zabel

One Broke Actress

Sam Valentine

REAL ONES with Jon Bernthal

Jon Bernthal

SAG-AFTRA

SAG-AFTRA

SAG-AFTRA Foundation Conversations

SAG-AFTRA Foundation

Second Act Actors

Janet McMordie

Six Degrees with Kevin Bacon

iHeartPodcasts and Warner Bros

SmartLess

Jason Bateman, Sean Hayes, Will Arnett

That One Audition with Alyshia Ochse

Alyshia Ochse

The 98%

Alexa Morden

The Acting Podcast from The BGB Studio

Risa Bramon Garcia and Steve Braun